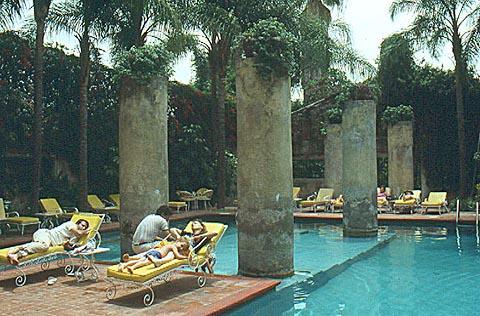

Staying at a Mexican hacienda hotel is like being transported back in time. The casa principal or main house usually stands before an elegant garden ablaze with purple bougainvillea and red flamboyant. The perfume of orchids fills the air. At some haciendas a massive brick aqueduct arches above and through its arches flows a cerulean blue swimming pool shaded by towering royal palms. Everything is of stone, tile or adobe brick.

The Mexican hacienda was a giant farm, under the absolute domination of an individual with powers often running back to a royal grant. Due to the underdeveloped transportation lines, the haciendas had to be self-sufficient. Along with the grant of land went a grant of Indians. As farm laborers they worked the lands and produced their own food. As carpenters, masons, blacksmiths, potters, weavers, they erected the buildings, kept them in repair, and fabricated all necessary tools and utensils. As servants they kept the owner — the hacendado — and his family from ever doing any work. Some hacendados were so wealthy that they could mint their own silver coins with their family’s crest.

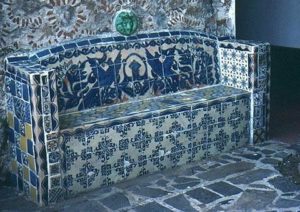

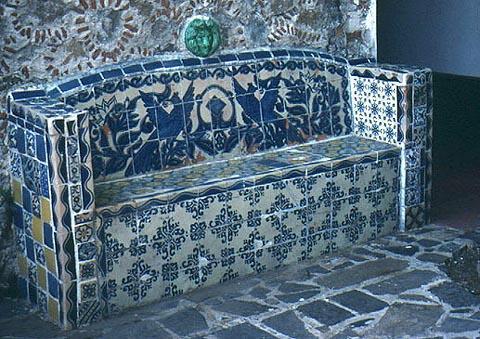

Residences often had 20 to 30 rooms, on one to three floors, including a salon, music room, billiard room, library, and dining room. Larger houses had two kitchens and two or three patios, with stone fountains, stone or wooden santos (statues of saints), potted plants, flowering vines, shrubbery and fruit and shade trees.

European art graced some homes, others were extremely Spartan, furnished only with a few leather chests, some hammocks, tables, chairs, wardrobes, and a plaster Madonna. With the passing of time, affluent and cultured owners acquired Italian bronzes, stained glass, Gobelin tapestries, and paintings by El Greco, Goya, and Murillo. Elaborate chandeliers hung in the dining rooms, and Venetian cabinets held Sevres porcelain.

The Jesuit and Franciscan missionaries sent from Spain played a key role in the brutal expropriation of lands from the Indians. Consequently, there wasn’t a single hacienda without a chapel, with a bell tower or spire.

The Mexican Revolution brought reforms. The former day-workers took possession of the abandoned manor houses and stripped them for building materials. Before long, these symbols of feudalism fell into decay and ruin.

Many of the great haciendas of Mexico, likened to and often built to resemble the chateaux of France, castles on the Rhine, or magnificent Italian villas have been rescued from decay and transformed into hotels, not the highly polished resort type, easily accessible by air, but luxurious out-of-the-way places that plunge the traveler into romantic old Mexico.

Staying at Hacienda Vista Hermosa, near Cuernavaca, is an experience. Begun in 1529 by Hernan Cortes, Vista Hermosa has had a long and tumultuous past. After Cortes’ death, his son, Don Martin arrived from Spain to take it over. The hacienda ownership left the Cortes family in 1621 and a series of eight more hacendados ruled Vista Hermosa before Emiliano Zapata and his followers evicted them in 1910, leaving it in ruins. Engineer Fernando Martinez found it in 1944 and created this luxurious refuge.

Vista Hermosa has served as the backdrop for many films, including the dramatic final scene of Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid where Robert Redford and Paul Newman “died” in a bloody battle with the Bolivian army. Film star, Anthony Quinn, here for another film, wrote in the guest book: “Whoever has dreams that aren’t fulfilled here ought to leave dreaming alone.”

Another former estate and sugar plantation of Hernan Cortes, Hacienda Cocoyoc is located nearby — Cocoyoc, means “Valley of the Coyotes” in the Nuahuatl language. To establish a firm hold on the land, Cortes married, Isabel, daughter of Moctezuma II and built Hacienda Cocoyoc in 1520 as a token of his passionate love for her. He added a chapel and aqueduct in 1600, and in 1613, the Count of Monterrey installed a sugar mill. The overseer of the cane fields lived in the mansion. Later, it became the site of the first Dominican monastery in Mexico.

An arch over an old wooden door at the entrance is engraved with the message: “The Door to the Paradise of America.” Considering that the temperature rarely varies from the high 80’s at noon to the low 50’s at night, the nomenclature, given by Antonio de Mendoza, first viceroy of New Spain, is justified. Rains usually occur in the evening during the summer, thus the mango grove-shaded golf course is always green. Paulino Rivera Torres, a Mexican businessman, restored it to its 16th-century grandeur over 30 years ago. Rooms, in new additions, are more modern. The hotel also features an excellent spa.

One of the most charming hacienda hotels is the Hacienda de Cortes, the Cuernavaca home of Cortes during his stay in Mexico. Located outside Cuernavaca in Atlacomulco, this all-suite hotel, also one of the smallest, has enough flowers, fountains and history to overwhelm almost anyone.

Known as the Hacienda de San Antonio Atlacomulco, it was begun by Cortes, who left it to his son, Don Martin. He made it into the most important sugar plantation in New Spain. It, too, became a gathering place for colonials, who loved to wander about its gardens, filled with somersaulting waterfalls and fountains. Later on, Emperor Maxmillian delighted in visiting the hacienda to take advantage of the fine weather around Cuernavaca. Eventually, the estate fell to the Cortes heirs, the Dukes of Monteleone, who gave new life to the lands. Unfortunately, their success was cut short with the advent of the Mexican Revolution. Today, the heirs to the title of Monteleone are buried beyond the gates. The hacienda sat in abandoned ruin until 1973, when Dr. Mario Gonzalez Ulloa transformed it into this charming hotel.

Dining at Hacienda del Cortes is a romantic experience. Here, amid the huge arches of the former sugar refinery with the sound of an enclosed stream that used to turn the mill wheel, waiters serve gourmet dishes to the accompaniment of a strumming guitar and candles flickering in the evening breeze.

One of the most authentic of the hacienda hotels is the 17th-century Hacienda San Miguel Regla, built by Pedro Romero de Terreros, the richest man in the world at the time. Located in the hills east of Mexico City in the Valle de la Huasca above the town of Pachuca, in the State of Hidalgo, it was named after the Province of Regla from which Romero hailed. Originally a gold and silver refinery, its former truncated ovens tower over the grounds, studded with oaks and pines, with a lake for boating and rose-lined paths for quiet walks. Graceful arches of the original aqueduct surround the patios and ovens.

Huge red iron doors frame a stone drive leading to a chapel adjacent to the casa principal. Trees, surrounding an old fountain, fill the main square. All 76 units have names. Double rooms lead off the main patio. Suites and villas, scattered throughout the grounds, feature a fireplace. Dinner at San Miguel Regla, served buffet-style without a menu in a long beamed-ceiling hall of the main house with a view of the garden, features hearty food. Delicious soups and simply prepared entrees topped off with rich desserts are the order of the day. And all meals are included in the price. Every Saturday evening, guitarists stroll through the gardens leading guests to an authentic medieval Spanish evening with wine.

Haciendas aren’t just hotels, but experiences that transform. Each revives and regenerates the energies of all who stay within their walls, reliving some of the grandeur that prevailed when the hacendados ruled the land.