Where are people and stories brought together from far-flung places around the globe? One place is MexConnect.com.

Several years ago my story about a quest for art treasures in Chihuahua was published here. I traveled there from New York with my daughter Elise to find artworks that were painted by my grandfather, the artist Ettore Serbaroli (1881 – 1951). We brought along some old photographs of ceiling murals that we were looking to find. Instead, what we discovered was an entire chapel that Serbaroli decorated in 1910 at an estate known as Quinta Carolina, which was built by a wealthy land owner named Luis Terrazas (1829 – 1923).

On the other hand, the ceiling murals in our old brown photographs had eluded us. In fact, we had almost lost hope that we would ever be able to identify where they were, or who commissioned them. And it would not have surprised us at all if we had learned that these beautiful creations were no longer in existence, perhaps in a building that was long ago demolished or that burned down during the Mexican Revolution.

But a couple of years after MexConnect published our story online, something extraordinary happened. I received this short email from someone who read about our adventure on the Internet.

Dear Mr. Serbaroli, my name is Loretta. I was born in Chihuahua, Mexico in a hidden gem, now Quinta Loretta. It is the name that my mother gave to the house because I was born there. I used to spend hours looking at the ceilings of my house wondering who was that man who signed as E. Serbaroli. The house has never been open to the public and we as family were very private. Now I live in England with my husband, who is English, and my two sons. Looking for more information about the artist that painted the ceilings of my home I went into the internet and I found that you went to look for them in Chihuahua, but I think you have not been yet in my house. I really would like to talk to you more about it, the paintings are in excellent condition considering the time and that they are in private home. I am very excited that I found you. Regards, Loretta.

I didn’t lose any time calling Loretta in England. I was as excited as she was that I could finally solve a mystery that had haunted me for so long. When we first spoke, it was as if we had known each other for years, because both of us were intimately familiar with those ceiling murals that had been painted a century ago. She told me that when she was young, it was like growing up in a museum, with decorative frescos on the ceilings as well as the walls.

Loretta said that the house was built by a wealthy man named Martin Falomir in 1912, who shortly thereafter fled to the United States during the Mexican Revolution. My subsequent research helped me create a profile of the man himself.

Before the Revolution, Martin Falomir (1868-1956), was a high ranking figure in Chihuahua’s politics and a business partner of Luis Terrazas in the mining company known as Compañía Minera La Virgen. He also owned a gas-works and a meat-packing plant.

Falomir must have seen the artworks that Serbaroli did at Luis Terrazas’ grand estate of Quinta Carolina, and commissioned him to do the murals on his own fabulous mansion that was under construction.

During my conversation with Loretta, I was relieved to learn that the two masterful ceiling murals had indeed survived in relatively good condition, despite so many years of humidity. Due to minor flaking in places, someone had done some touching up of the paint. I asked if the family would allow us to get a few photographs of the murals, and she agreed. I contacted my friend Francisco Muñoz in Chihuahua, who generously offered to stop by the home and take a few digital photos. He did, and for first time, we were able to see the true color scheme that Serbaroli painted almost a century ago.

The large ceiling mural for the living room is packed with symbolism. Its subject matter, as might be expected, is related to wealth and prosperity. It tells a story of “temptation” — the struggle of Virtue over Vice. Central to the image is a young woman reclining with her legs crossed. On the right, at her feet, is a little cherub with a jewelry box, who is preoccupied with a string of pearls. Directly opposite on the left hand side are two other cherubs who appear to be pulling the woman away from the sin of avarice. One of them prominently holds a peacock feather, used often through the centuries as a symbol of incorruptibility and immortality. In Christianity, the peacock is an ancient symbol of eternal life. The woman’s face has an enraptured expression as if she is being lured by wealth and pleasure. Her left hand is strategically placed as if she is tempted to uncross her leg. The cherub above is trying to catch her attention with the feather of incorruptibility. The cherub below is attempting to lead her away from the lure of riches.

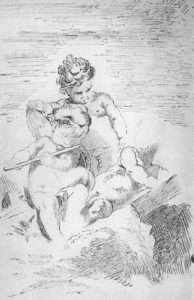

The other ceiling also features cherubs, which are reminiscent of great Italian masters such as Tiepolo. They are scattering flowers from cloth, a sign of celebration, perhaps because Falomir may have given the home to his wife as a wedding present. A butterfly appears in it as well, which often symbolizes a transformation in life, but also represents joy and bliss in people’s lives. Serbaroli had sketched cherubs into the pages of a small, red leather autograph book that belonged to his wife Josefina. Such books were popular before hand-held cameras, because friends could record their thoughts in them as mementoes of memorable times spent together. (See more on the autograph book in Discovering Clues to the Legacy of a Mexican Poet). The sketches were undoubtedly part of his concepts for the ceilings. He would have drawn them during discussions with Josefina about the designs he was contemplating for the murals at Falomir’s luxurious mansion. One of Serbaroli’s cherubs in his wife’s autograph book is looking into a mirror, a symbol of vanity. Serbaroli was probably considering this for the large ceiling mural.

He was totally committed to the art he was commissioned to do. Often, walking the streets of Chihuahua, he focused his thoughts on the task, hoping that a fleeting bit of inspiration, like the butterfly he painted, would present itself. Or perhaps he would conjure up a face, a posture or some idea that he could incorporate into his works. And now Josefina was his muse, someone with whom he could share his thoughts and ideas — helping her visualize them by putting them onto whatever paper they had at hand.

Yet it was exactly politics that ultimately interrupted his life.

While living in Chihuahua, the Mexican Revolution disrupted the region. The ensuing turmoil threatened Serbaroli’s profession and his existence as well. President Porfirio Diaz, who had ruled Mexico for more than thirty years, was deposed in May, 1911. The next year, Serbaroli’s principle employers Luis Terrazas and Martin Falomir fled Mexico for the safety of the United States. Architectural plans and investments in new building structures came to a sudden halt. Pancho Villa’s army, in support of President Francisco Madero, invaded Chihuahua in March 1912 and scores of men were killed in the streets.

President Madero, who deposed Diaz, was executed in February 1913, and his brother Gustavo was later beaten to death by supporters of the new regime under General Victoriano Huerta. That same month, Huerta had the new governor of Chihuahua, Abraham Gonzalez, arrested. In March, Gonzalez’ lifeless body was found alongside a desolate stretch of railroad tracks, and on and on it went. The sharp, cracking sounds of rifle shots, and even exploding artillery shells, became commonplace in the city and surrounding hills.

In December 1913, Serbaroli was forced to flee the country because he was an Italian citizen, and Pancho Villa had ordered all foreigners to leave northern Mexico. He left, bringing his wife, his infant daughter and his mother-in-law out of harm’s way to the border station at El Paso Texas, where thousands of people had settled in makeshift refugee camps along the canals.

They moved on to California where Serbaroli found work in San Francisco at the Pan Pacific Exposition of 1915. He later painted frescoes and ceilings at Hearst Castle in San Simeon (1925-27) and eventually at the Hollywood studios of Warner Brothers, RKO Pictures, 20th Century Fox and others (1928-48).

He never looked back on the artistic creations he left in Mexico. Instead, it was left to me to look back for him and piece together the puzzle of where they are located.

When my daughter Elise and I visited Chihuahua, it seems that we actually were very close to where the ceilings were located. We had, in fact, walked right past the magnificent house never knowing that my grandfather’s paintings were concealed behind its doors. We were so close, yet we never knew it.

It took the modern day marvel of the Internet, and an answer from someone thousands of miles away in England, to help us find them in a home in northern Mexico. Now, because of that technology, we not only know where the artworks are, we know why they are there, and how they came to be painted by the artist a century ago. Moreover, we have found new friends and acquaintances with whom we can share these artistic treasures. Thank you MexConnect!

The author would like to thank Loretta and her family for allowing access to her beautiful home. Also Mr. Francisco Muñoz, historian, art aficionado, and great grandson of Luis Terrazas, who was kind enough to take photos of the murals, some of which are pictured in this story.

Mr. Serbaroli, I hope this comment finds you well. I may have some additional information regarding the grand residence that contained the ceiling murals painted by your Grandfather. The grand residence I am referring to is that of Mr. Martin Falomir, constructed around 1912. I have uncovered some documentation that links an American Architect named George F. Barber (1854-1915) to this Chihuahua residence of Martin Falomir. I am reaching out to you to seek additional information regarding the location of Mr. Falomir’s residence, so I can research that building further. Would you be able to share with me the street address of this residence? Perhaps you took some photos of the exterior of this building that you can share with me as well. Hope to hear from you soon.

Hi Chris, would like to speak with you about the house, but don’t know how to get in touch with you. Joe Serbaroli