San Felipe is the center of a living museum that has witnessed the passage of a continuum of men, women and children for the past 2- to 3,000 years. Whereas evidence of their existence remains in most of the canyons draining the nearby Sierra San Pedro Martir, it stands in abundance in shell mounds lining the 50 miles of shoreline from Punta Estrella to Puertecitos.

Fortunate for those who seek such things, they appear to most as useless scatterings of sunbleached seashells. On the contrary, those seemingly useless shells are the visible remains of a 15-centuries-long story of life in the good old days… before you and I came along with our shoes and ships and sealing wax.

There is, between 2 and 300 meters from the shore at Playa Punta Estrella, one of the largest shell mounds in Baja Norte. More than 1,000 feet long, it is composed mainly of clamshells. You’ll find it on the north side of the sandy access road to the beach where the first line of shrubbery appears. And, a mile farther south, there is another, at Poblado Gutierrez Polanco.

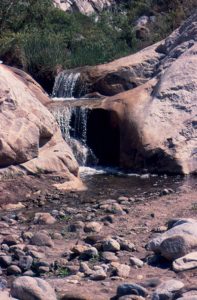

Knowing the Indians were clannish, you can look west from the Punta Estrella shell mound to see Arroyo Chanate 10 miles distant, and Arroyo Huatamote west of “Polanco,” each of them representing avenues of access. Considering these avenues as funnels; lines drawn from the mouth of each will encompass a group of canyons in which the several clans lived.

A line drawn through the north-south center of these two shell mounds, connected to other mounds farther south, will show where the shoreline was 1,000 and more years earlier. What’s more, although shell mound excavation can be labor-intensive, it is a task that can yield stunningly rewarding results. I, for example, have removed so much obsidian from one that I began to envision adolescents making spear and arrow points while their parents dug and shelled a bountiful harvest. In fact, like a family at a backyard barbecue, I see them milling about the beach, each with his and her own task to perform.

As I stood at Punta Estrella conducting research for a story, I chanced to look up where, under a typical azure sky, I saw a sight similar to one the Indians must have seen time and time again. There above the trees were a dozen hawks searching for a midmorning feast. They’ve always been here, you know, the redtail, the golden, the Mexican black.

Ever see a hungry redtail swoop down on a pigeon? There is no difference between that hawk carrying off a pigeon and you or I or an Indian harvesting shellfish. Death is a part of life and the perpetuation of the species. Thinking of death, you may not like the ubiquitous turkey vulture but they are the cleaning crew, the ones who remove the carrion. Ever watchful, they glide in daylight effortlessly on wings that carry them over the shore as often as they survey the desert. Look for them at sundown and you’ll find four, five and six of these bulky black redheads roosting comfortably on a single cardón.

Speaking of cardón cactus, find the “Valley of the Giants” (9 miles south-southeast of San Felipe), and you’ll find a totally different scene. The king of all cactus, many of the plants seen here are between 200 and 300 years of age. By the time you’ve seen enough of them, you’ll know they are nesting places for the larger birds — the hawks and herons, the vultures, eagles and osprey.

See them in early spring when they display white-shaded trumpets for bats and bees and hummingbirds to feast on a nectar placed where pollen has a chance at reproduction. Return in late spring to see one of the mysteries of life: For all the white-shaded trumpets there were you’ll see but one four-petalled seedpod per plant.

Some plants cast their seeds on the ground while others create seeds so light they float on the wind. Cardon’s little black seeds are for carrying in the belly of a bird to some new place where it can fall to earth to find protection in the shade of a totally different plant. If you’re looking for young cardons, the little ones from one to ten years of age, you’ll have to search under or within those other plants. But there’s another side to these gentle giants — their bone-dry skeletons you may never have considered. Find one and there’s a 50-50 chance you’ll be looking at a plant that germinated before the first Spaniard set foot on the San Felipe.

When you think about San Felipe, you probably think about a distant desert community nestled under the lee of an old volcano; but if you think about the San Felipe, you’ll be thinking about a place as different as night is from day. Remember the shoes and ships and sealing wax? They were, in reality, here before us.

Indians made their shoes from maguey. There are two Spanish galleons buried in the sands of the San Felipe and desert beehives contain an acceptable form of sealing wax. The fact is, they’re all here, these magnificent things we speak of, plus many we haven’t had time for, waiting always, waiting for those who enjoy… a living desert museum.