Good Reading

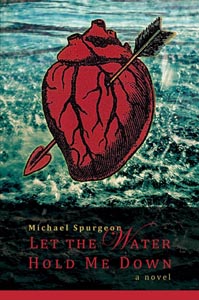

Let the Water Hold Me Down

Let the Water Hold Me Down

By Michael Spurgeon

Ad Lumen Press, American River College, 2013

Available from Amazon Books: Paperback

Michael Spurgeon has written a remarkably fine novel.

Let the Water Hold Me Down has the makings of a classic. It is written with skill and with grace, and the old verities that are at the heart of being human are here: loss and grief, guilt and longing, loyalty and love.

Set in modern-day Mexico, Let the Water Hold Me Down tells the story of Hank Singer — what happened to Hank after he lost his beloved wife Jenn and their three-year-old daughter Suzy in a canoe accident one spring in Colorado, caused in part by Hank’s youthful insistence that the rapids posed no real risk.

It is also about his relationship with César Lobos de Madrid, whose “family was one of the oldest, wealthiest, and most politically connected in Chiapas, if not in all of Mexico.” In college Hank and César were the “big men on campus,” “Batman and Batman,” leading their soccer team to the division championship. “We were best friends, and it turns out I didn’t know him all that well either.”

After college, César played professional soccer for Cruz Azul in Mexico and was a rapidly rising young star until a tragic leg injury, resulting in a rod and five screws in his leg, destroyed his soccer career. He tells Hank, “I was going to be great…. It was a fact… and then it was gone.”After college Hank moved back to Denver, met a charming young woman on a ski lift, married her, went to work for her father’s construction company, had a beautiful daughter, and then suddenly all collapsed in a few minutes in those rapids on a Colorado River. Hank reflects: “I realized that he had lost something that I couldn’t really understand just as I had lost something he couldn’t comprehend.”

Hank had been deeply in love with Jenn, even loved her addiction to blonde jokes: “Why’d the blonde climb the chain link fence? To see what’s on the other side.” When Suzy was born, Hank asked César to become godfather… “we called each other ‘compadre’ just like we might call each other buddy or pal.” In Latin cultures, it’s a sacred trust: “Once a man’s your compadre, no matter what happens, he’s always your compadre. You’re family, brothers for life.”

The plot thickens.

Hank resigns from his father-in-law’s construction firm to move to Chiapas, without “deliberate purpose” to live with César in a Lobos family compound in San Cristóbal, although they had seen each other only once in the seven years that had passed since graduation. In El Acuario, a popular bar where Hank, partly out of boredom and partly out of a desire for some independence, decides to work, he begins to fall in love with María, the barmaid, and “I thought she might have been the most beautiful woman I’d ever seen.

It turns out that she was a former lover of César, largely because her wealthy family and his wealthy family were trying to force a marriage to create a lucrative economic alliance. Impregnated by a political activist working against the interests of her father, María was disowned. She has a three-year-old daughter, Luz. When César discovers Hank’s relationship with María, he is outraged, “You stupid, stupid fuck. I told you to stay away from her.”

Beyond the developing personal complications that test both loyalty and love, Hank has arrived just a few weeks before the Zapatista uprising in Chiapas, led by Subcomandante Marcos, who on January 1, 1994, declared war against the government and the military. Lying next to María, Hank wakes up early that morning to see several hundred Indian soldiers in the zócalo, the central plaza below their balcony, “many of them women and young teenagers,” some with only toy guns or sticks or machetes, most covering their faces with ski masks or red bandanas. The fair-skinned Subcomandante, in a Spanish “clear, articulate, and educated,” announces that they are El Ejército Zapatista de Liberación Nacional, the EZLN.

One reason so many scenes in this novel make you feel like the author was “there” is because the author was there, living in San Cristóbal at the time of the Zapatista uprising.

Hank, encouraged by his liberal friends at El Aquario, begins to ponder the huge social issues at work, to which he is becoming a witness, and against his will perhaps even a participant. He had already visited the huge ranch of the Lobos where he noted that “The servants seemed invisible to them. With me, as I’m sure was true with all his guests, César’s father was almost impossibly polite and gracious, but I never heard him say please or thank you to a single servant. Not once.” The centuries-old holdings of the Lobos family cover “almost ten thousand hectares [around 2,500 acres], with “something like six thousand acres of coffee and thirty-two hundred head of cattle.”

The Indians have nothing.

The heavily armed Mexican army soon moves into the zócalo and Hank comes “to understand on a visceral level that no matter what rights you think you’re entitled to, the truth is the people with the guns decide.”

Decades ago, a kindly scholar, of the old school, told me the great stories, for thousands of years, usually take place in turbulent times, and are about loyalty and love. Hank learns a lot about loyalty and love during the difficult days in San Cristóbal and Chiapas. He also learns that doing nothing creates consequences just as deliberate choices do and that, even though friendship ends, loyalty remains. He also realizes “how wrong my college postmodern literature professor had been when he said romantic love doesn’t exist”… and he discovers “there is astonishing beauty in hearing a woman whisper your name as she quietly climaxes in another language.”

Put this one on the top of your list.