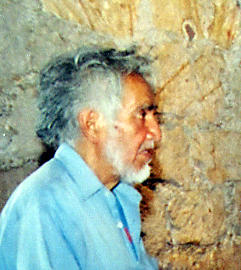

Saulo Moreno Hernandez is a 71 year old sagacious, self-effacing artist from Tlapujahua, in the state of Michoacan. One of his works is featured in the Americas Gallery of the British Museum in London. One of his early ‘calaveritas’, which are imaginative statues of skeletons depicted as alive and in various poses and garb, was bought by Diego Rivera years ago and is now in the Diego Rivera museum in Mexico City. He has represented Mexico in international cultural exchanges in London and Japan. A painting Saulo did years ago for a movie set when he worked for the Mexican film industry now hangs in the home of a wealthy Parisian. In some discussions of Mexican art, his name appears alongside those of Siquieros, Orozco, Tamayo and Rivera. “The details of who has my works and what they might have paid are not important to me”, he says. “What does mean something to me is that a concept that came from my soul is giving pleasure to others”.

Very few people in Tlapujahua know him by name. He seems to be somewhat of a pariah because he’s an old man with a wife young enough to be his daughter. And he has the appearance of a “rag-picker”. An interviewer who published an article about him in a southwestern U.S. newspaper described him as an eccentric Mexican artist. But he is totally unaffected by all of this, perhaps because it is hardly different from the solitude and alienation he experienced when he was growing up long ago in Mexico City.

He has been an avid reader since childhood. Most of his creations are figures of animals, many of them chimeric, manifesting his rich imagination as well as an artist’s sense of form and movement. There are strutting roosters and graceful giraffes. There are fantastic, fantasmagorical surreal menacing creatures which are part insect, part mammal, part crustacean, part reptile. They are sturdy by virtue of their wire armatures over which are formed a paper-maché type “skin-flesh” that is then primed and richly painted. Their sizes vary in height from between eight inches to thirty inches. They sell for far less than they should. They are truly works of art.

During his early years in Mexico City, he studied art in several institutions including the well-known Mexican National School of Plastic Arts also known as San Carlos. He worked under a famous South American professor of art who in return for Saulo’s talented help taught him many practical art techniques.

He laughingly admits that he doesn’t worry about how his appearance is perceived by others. His meager income and lack of savings disallow fine clothes. There is no running water in his home.

He was walking with two of his children one day on the main street in Tlapujahua. A stranger held out his hand and dropped ten pesos in Saulo’s hand. Saulo thanked him and put the coin in his pocket, wondering what made the man give him the money. His son asked him why. He assured the boy he didn’t know but certainly hadn’t asked for it. Saulo tells the story with wry amusement. He says the event serves as an anecdote about appearances being misleading and judging by what we see on the surface of a thing or a person, thus missing its essence.

He amplifies his thoughts on this: Frida Kahlo was once described by the wealthy nephew of an ex-president of Mexico who met her in her bedroom when she had become bed-ridden. When asked his impression of her, the man said her room smelled of tequila and described her as a drunk and an alcoholic. Saulo emphasizes that this was a shallow comment on a gifted artist whose work came from the depths of her soul. It totally ignored her real essence.

He was born in Mexico City in April 1933 of extremely humble origins, not sure of the exact date because in those days record keeping was inexact. He feels that his early artistic inclination derived from being without many friends as a young child, forcing him to be introspective, to live within himself. His earliest memories are of walking around his neighborhood picking up discarded materials like pieces of wire and fragments of wood and then using them to create things. People denigrated his projects as a waste of time playing with garbage.

His first creative output directed toward earning money was the making of the skeleton-like figures, the calaveras or “calaveritas” as he fondly calls them. Similar to the Day of the Dead ‘caterinas’, which are typically skeletal figures, usually male, sometimes female, in fancy outfits, the “calaveritas” are skeletal creatures depicted engaging in different activities in every day clothes. However the terms resist more exact definition and tend to overlap. Saulo muses that something he can’t put his finger on compels him to create these figurines. Friends who help him sell his work often tell him there is more potential income in the fanciful chimeric animals. But he is always drawn back to the others saying although he can paint he much prefers doing the calaveritas.

It takes between one to two weeks of work to complete one of his creations. He starts with malleable, galvanized wire, molding it with his hands to create a wire-frame figure, wrapping his finger-tips with masking tape to protect them from injuries. He learned the need for this the hard way early in his career. The wire-frame model serves as his “sketch”. The gauge of the wire varies according to the ultimate size of the creature.

As the piece takes shape and he starts to perceive its proportions, he often finds himself deviating from the image in his mind to something else so that the end result differs from the original intent. This phase is usually completed in one and a half to two days.

The next phase involves the use of brown wrapping paper. He assures me it is the same paper used to wrap fresh tortillas. He wets the paper and crinkles it, then straightens it. He usually has to do this several times to get uniform moistening. Then as the paper is unwrinkled, he begins applying it in layers. He likens this phase to sculpting.

Step three involves drying the wrapped armature. This is the most crucial. If the drying is less than uniform or in any way incomplete, it causes the wire frame to bend, changing it’s shape.

He described the evolution of his technique, laughing at himself for his errors and failures. Early in his career, he used charcoal for drying but it was prohibitively expensive. He then bought an electric hotplate to try. He was living in the home of a friend in Mexico City. He plugged in the gadget and watched sparks fly. All the lights went out. His friend called to him from another room telling him that he thought a circuit had blown. Saulo laughed heartily as he related this. “I know”, he called back. His next attempt was a small gas water heater which he bought used. But it also failed to dry his productions adequately. He eventually settled on the cheapest and best, which is sunlight. He knows that an electric oven would be ideal but he can’t afford one. He bows to the occasional unpredictability of the weather and seasonal changes. Adequate drying must be judged by touch and tapping with his fingers. He affirms that the sound and feel of the contact with the object tell him what he needs to know to be able to proceed.

Then he applies a watery mixture of glue and ‘blanca de españa’, a kind of primer, with a brush. It must again go through a drying stage. Then he paints it. Over the years he has experimented with different types of paint and now uses an automotive type of acrylic paint. If he doesn’t want a shiny finish, he mixes it with a special compound to dull it.

He continues to modify his techniques. He quotes a Mexican proverb: “Renovarse o morir” (Continue to change or die).

Then comes the gut-wrenching part, converting his work into food and clothes for his wife and five children. She is forty-six years younger than he. His oldest child is fourteen. When he talks to her he calls her “Mi hija” (my daughter). And, indeed, when she speaks about him, it is with obvious respect, almost if he were her father.

One problem is a that a large majority of Mexican people disparage the Mexican folk art. Another is the often suffering, frequently vacillating Mexican economy. Saulo lives about two and a half hours by bus from Morelia. He used to take his work to the ‘Casa de Artesanía’ there but the merchants would pay him a pittance if anything at all telling him to come back in a week or two. He loses a day of work every time he makes the trip. He knows a couple of gallery owners in San Miguel de Allende and if one of them comes to visit him in Tlapujahua he can make some quick sales but they come infrequently. To travel there would force him to lose two days of work. He still occasionally takes his wares to Morelia and deals with one of the government sponsored agencies like ‘Fonart’ that will give him a cash advance on sales but they pay very low prices.

Consider this: he might sell a piece that has taken him two weeks to create for $200 dollars. In overall income this would come out to be a little under $5000 dollars a year. This allows him to live in a hovel without running water, with shabby vestments for himself and his family, no savings for the future or for emergencies, and scant hope for improving his lot. And he doesn’t complain about it.

He bristles at being called an artist. “Me, I’m an artesan. Maybe I’ll be an artist someday but for now I’ll continue to learn my craft.” One senses his comment to be a bit tongue-in-cheek. He reminds me of Plato in a poor Mexican’s clothes.