Sometimes in the evenings, after the sun has set behind the monolith that towers over the small village of San Sebastián Bernal, ánimas, or restless souls who sleep in the small graveyard near the old chapel, rise up and move silently through the quiet streets.

The ánimas mean no harm. They are just continuing their daily round – what they did when they were alive.

“They carry candles that light up their faces and they’re going to the small chapel in the old part of town,” says Claudio Brusadin, who has never seen the ánimas but has talked to people that have including, he says, the mayor of Bernal and his wife. “Once they get there, they go in and pray and then return to the cemetery, which has been here since the town was founded.”

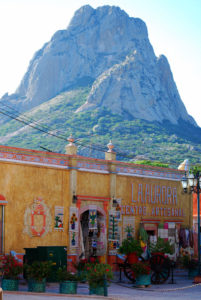

On the soft, gentle evening when my friend Yusfia and I are sitting in Claudio’s restaurant, Piave, on Avenida Zaragoza in Bernal’s central district, I see no ánimas walking to or from church. Instead, Bernal is alive with the calls of a young boy balancing a bread-filled basket on his head as he walks up the street selling his wares. Families sit at the streetside tables at Tia Le Millita, a corner restaurant, and young children play ball in the churchyard. Bernal, Querétaro is a delightfully charming 16th century colonial village, whose buildings are painted in the colors of a Mexican sunset – ocher, soft yellow, sienna, rich orange and dusty rose.

I have come to Bernal because it is one of Mexico’s Pueblos Mágicos. These magical towns are designated such because of their historic charm, peaceful atmosphere and closeness to a major city, in this case, the state capital, Querétaro. I am on a quest to visit as many of the Pueblos Mágicos as I can. There are 35, each similar in its heritage and yet also distinctly unique.

But it may be Bernal that has the most interesting topography. Here the the Peña de Bernal, a rock monolith some 10-million years old, juts out of the earth and rises almost 350 meters high.

“Many say that peña gives off energy,” says Claudio, an Italian who trained as an electronic engineer in Switzerland. He moved first to Mexico City and then to Bernal to pursue a culinary career. “Bernal gets very busy during the Equinox when people come from all over to take part in the energy rituals.”

Claudio tells us that the peña is the third largest in the world. It differs from a mountain, he says, because there is no dirt or vegetation on the rock. It is just a sheet of rugged outcroppings of stone.

The energy I am feeling comes not from the Peña de Bernal but from sipping an espresso at the end of a long day. We had driven south from Querétaro after a leisurely breakfast in the courtyard of the beautiful Santa Rosa Restaurant on Independence Plaza. Our first stop was Cavas Flexinet, a Spanish winery, located just outside of Ezequiel Montes.

The winery offers tours, so we followed a group of college students through the bottling area and down into the brick lined tunnels where thousands of bottles and casks are stored. Back upstairs, the students quickly buy glasses of wine and sandwiches from a small deli, which also sells some of the cheeses made in the area. They then disperse around the flowing fountain to small tables set in the shade. I take a few sips of the wine, which is sold only in Mexico, and then head with Yusfia across the street to our next destination, Los Azteca Hacienda Mexicana.

Marco Antonio Jaimes and his wife Yadira Gonzalez are there to meet us when we pull up in the dusty drive. Yadira tells us that Los Azteca, which dates back to the 1700s and is also a winery, is a lienzo charro, where Mexican style rodeos are held. On busy days, hundreds of people arrive to watch, but today it is only us and the 20 or some horses that are part of the ranch. Marco, dressed in the uniform of a charro or gentleman cowboy, demonstrates the Cale de Caballo or Test of the Horse, in the large arena. Tlaloc, his horse, is named for the god of rain. The horse is a national champion and responds easily to Marco’s unspoken commands. Indeed, Tlaloc and Marco are so in sync, that most of the time he doesn’t even need reins to get the horse to perform his “tests.”

Afterward, we enjoy a sip of their wine before we’re off to dine in the outdoor gardens at La Ronda, another winery just down the road. This one is Italian, and it is here that we first meet Claudio, as he often cooks meals for visitors at the La Ronda on the weekends. Today, he has created a carpaccio of thinly sliced tuna topped with artichoke hearts and arugula and sauced with a mango vinaigrette. This is followed by flambéed shrimp atop a squid ink risotto; there is tiramisu for dessert. One of the winery’s eight wines is served with the meal. After we’re done eating, it’s time to take another tour.

One of La Ronda’s specialties is growing grapes to make Kosher wines that are sold only in special markets in Mexico City. The vineyards here stretch for 167 acres, off into the distance where blue-black mountains line the edge of the landscape. We also take time to wander through the vineyard’s extensive cactus garden, following the winding pathways that meander through cacti samples from both Italy and Mexico.

I would love to linger by the gazebo or the fountain at La Ronda, or, maybe best, in the tasting room, but I want to get to Bernal while the light is still good. And so we say goodbye. After tucking my bottle of Cabernet Sauvignon into my vast mesh bag, we head out to Bernal, about a 20-minute drive. Yadira told me that I could rent a horse at Los Azteca and ride cross country to Bernal, about a 15 minute trail ride – something I would love to do when I come back. She says they frequently have visitors who head into town for a lunch or dinner and then ride back through the sage and cactus desert.

Indeed, horseback riding is common in the area. In the town of Cadereyta de Montes, we see a band of men wearing crisp white shirts, who are riding through the town, stopping at a convenience store to stock up on bottles of water and then buying freshly cooked corn, painted with butter and spices, from a street vendor. They are part of a group that meets once a week to ride between the towns.

As we drive, Peña de Bernal grows bigger, looming large over the landscape. But when we head down the cobblestone street that leads to the historic district of Bernal, I almost forget the monolith and instead am overwhelmed by the charm of the town. It is picture perfect. But I have to admit that, despite its allure, one of the first things I want to do is find a shop that sells the brown opals mined near here. I’ve been told they are both beautiful and inexpensive.

The first store I find that lists opals on its outside wall is closed. Am I too late, I wonder? I ask a young woman if she knows of another place selling opals and she motions me into her shop, Artesanías La Peña. It’s a small store, cool compared to the warmth of the day. The shop is filled with glass-covered cases loaded with opals in rich earth colors of oranges, browns and yellows. Watching as she brings out trays of earrings and necklaces, I am almost overcome by the choices. I finally settle on a beautiful necklace with delicate dangling opals and matching earrings. The prices, indeed, are reasonable and I know that I am wearing something that is natural and from the nearby earth.

My opals secured, I head across the street to the San Sebástian Mártir Church, built between 1700 and 1725. This is a good place to start my stroll through Bernal and I wander through the courtyard, admiring its calm and beguiling beauty. My guidebook tells me that the masonry in the bell tower preserves the handprints of those who built the church.

Across the street is El Castillo, another colonial structure. This one, in washed shades of pale orange accented with pink, contrasts nicely with the vivid oranges, reds and yellows of the church. The striking German clock tower is a 20th century addition to the 18th century building that houses the municipal government.

The centro or central district is small, but crammed with shops offering a unique variety of goods. La Aurora Centro Artesanal has wall hangings and clothing. Bernal is known for its woolen goods, and artisans with weaving skills create rugs, shawls, cushions, bedspreads, jackets, sarapes, dresses and ponchos. Just down the street, Artisans La Esperanza features religious art, including what look to be elaborately carved and ornately studded church doors. Alas, there’s no way to put those in a suitcase to take on the airplane.

Because Bernal is known for its candies, we stop at Dulces Artesanales Peña de Bernal, a delightful candy store that sells the locally made apple wine and a variety of candies including candied cactus fruit and traditional dulce de leche de cabra (a goat milk candy) whose varieties include strawberry, guava, walnut, fig and sesame seed. Unable to decide what to buy, I settle for a package that contains all the varieties as well as a packet of obleas con cajeta, thin wafers separated by a thick layer of sweet milk candy. The candy factory is just down the street and Claudio tells me they offer tours.

The town is also famous for its blue corn gorditas – rounds of masa stuffed with a variety of fillings. But we had promised Claudio that we would meet him at his restaurant and so we wander past the market building with its broad courtyard where farmers bring their produce to sell each morning. It is empty this early evening, but we stop to look at the murals painted on the walls that celebrate the community’s agricultural roots.

Bernal boasts some of the Moorish influence, called Mudéjar, brought over when the Spaniards ruled Mexico and common in many colonial cities. It can be seen on Avenida Zaragoza in the tiles covering the front of Casa Tsaya, a hotel with a charming courtyard restaurant next door to Piave.

Claudio tells us that the building where Piave (Italian for “river”) is located dates back to 1730 and was once a meson or mansion owned by the Floris family. It now is a rambling restaurant with several rooms, including a courtyard. An interesting feature, says Claudio, is the entranceway where murals are painted on all the three walls, the entwined flowers slowly fading. The murals, he says, are over a 100 years old.

But a century is just a moment ago in Bernal, which was founded by Captain (some say he was a lieutenant) Alonso Cabrera of the Spanish Army. He came here in 1647 with ten soldiers and three of his sons in order to protect the locals in this hostile terrain. Some time after that, a chapel was built on the peña; it becomes a focal point during the festival of the Holy Cross, each May 1 to 5th when thousands come to the town.

“The Day of the Holy Cross is our main festivity,” Claudio tells us as he makes one of his menu items, Insalate Anne – lettuce, avocado, grapefruit, crabmeat and green apples in a vinaigrette. “That’s when they bring the Holy Cross down from the top of the peña.”

Thirty or forty escaloneros are chosen for the task. The criteria, says Claudio, is that they must be good Christians. And they must be strong ones, too, for the group passes the cross down the hill and then carries it through town. But they don’t stop there. According to Claudio, the escaloneros then travel with the cross to other surrounding towns, part of the week long festivities which have been going on for centuries.

There’s a mystical feel for what the monolith emits though it’s hard to pinpoint what exactly causes that energy. It may be the mythical snake that lives in the center of the peña, the core of amethyst and other crystals which some say lay beneath the rock or it may just be the beauty of this little town, tucked into the highlands of Central Mexico.