The only thing that is definitely known about Subcomandante Marcos, the ski-masked mystery man who leads the Zapatista rebels in the jungles of Chiapas, is that he is an intellectual. Conflicting sources who assure us that they know the true identity of the man behind the mask have variously identified him as a disillusioned government official, a university professor and a Jesuit priest.

One thing these rival Marcos spotters do agree on, is that he functioned in an area requiring a certain amount of gray matter before launching his career as the Robin Hood of the Lacandon rain forest.

This favorable assessment of Marcos’ mental acuity is shared by foreign observers, Alexander Cockburn, the acerbic English Marxist who writes a column for The Nation, rarely has anything but disdain for the intellect of other writers. But he was so impressed by a collection of Marcos communiqués reprinted in California’s Anderson Valley Advertiser, that he described them as “55,000 words of some of the most savagely eloquent prose in the history of Mexico.”

The closest look that most of us have had at Marcos was when he was interviewed earlier this year by Ed Bradley of the “60 minutes” team. In the course of the program it came out that Marcos speaks quite passable English. Not only that but it appears, from Bradley’s comment, that the Subcomandante also granted interviews where he communicated in Italian and French. Nor was the professorial aura diminished by the spectacle of Marcos reflectively puffing on a pipe during the interview.

I mention all this because comparison is inevitable between this Zapatista movement and its predecessor in the early years of this century. Marcos is not just a político out to seize power. He is a revolutionary and make no mistake about it. Though he may not be from Chiapas originally, the extent to which he has made the cause of Mexico’s most exploited state his own is evident from this excerpt from one of his communiqués:

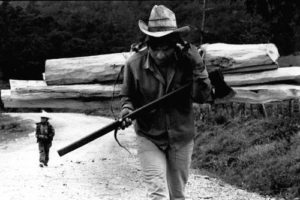

“The natural wealth that leaves these lands doesn’t travel over just these three roads (leading to Chiapas). Chiapas is bled through thousands of veins: through oil ducts and gas ducts, over electric wires, by railroad cars, through bank accounts, by trucks and vans, by ships and planes…And what tribute does this land continue to pay to various empires? Oil, electric energy, cattle, money, bananas, honey, corn, cocoa, tobacco, sugar, soy…and Chiapan blood flows out through a thousand and one fangs sunk into the neck of southeastern Mexico.”

Now let’s look back some eighty years. The leaders of what has become known as the Mexican Revolution were Francisco Madero, Venustiano Carranza, Francisco Villa, Alvaro Obregón, and Emiliano Zapata. But were they revolutionaries or simply rebels? The two are not the same. Rebellion, as Webster defines it, is “organized, armed, open resistance to the authority or government in power” while revolution is a “movement that brings about a drastic change in society.”

By this standard, Madero and Carranza were rebels – Madero against Porfirio Díaz, the old dictator, and Carranza against the usurper Victoriano Huerta. But neither one had any sweeping program for improving the lot of the campesino or the urban proletarian. Villa and Obregón could be described as rebels who were also social reformers. Obregón’s administration enacted agrarian, labor, and educational reforms while Villa propounded a plan for a complex of military-industrial colonies that would provide a pool of citizen-soldiers who doubled as workers.

Zapata was the only true revolutionary. What chiefly distinguished zapatismo from maderismo, carrancismo, and villismo was a remarkable declaration of principles called the Plan de Ayala. Proclaimed November 24, 1911 it contained the most radical platform in Mexican history. Where Madero and Carranza had shied away from the land question, the Plan de Ayala boldly called for expropriation by degree (more on landowners who supported the old regime, less on those who didn’t) and pensions to widows and orphans of men killed in the Revolution.

John Womack, author of a definitive study on Zapata, describes the Plan de Ayala as “garbled and rambling, without a hint of metropolitan grace.” Wordy, repetitious, and dotted with misspellings, the Plan was considered a joke among the educated. Particularly farcical was the nomination of Pascual Orozco as “Chief of the Liberating Revolution.” Orozco, Mexico’s version of Benedict Arnold, would later sell out to the Chihuahua cattle barons and join forces with Huerta, the military adventurer who overthrew Madero and engineered his assassination.

So lightly was the Plan de Ayala taken that Madero, who is reviled throughout the text, gave Enrique Bonilla, editor of Mexico City’s Diario del Hogar, enthusiastic permission to print it. “Yes,” Madero told Bonilla, “publish it so everybody will know how crazy Zapata is.”

For all its limitations, the Plan de Ayala is still the most authentic popular manifesto in Mexican history. Its very literary ineptitude attests to its genuineness and ties to its constituents, the downtrodden peasants of Morelos.

Then a curious thing happened. The zapatista coalition, which began as a mass movement of uneducated peasant farmers and agricultural laborers, became co-opted by a group of sophisticated left-wing intellectuals in Mexico City. These men were urban radicals, some with socialist and some with anarcho- syndicalist backgrounds.

Best-known of these zapatistas-by-adoption were Antonio Díaz Soto y Gama, Rafael Pérez Taylor, Luis Méndez, and Miguel Mendoza Schwerdtfeger.

The flavor of this migration was captured in one of Hollywood’s better portrayals of the Mexican Revolution. This was the 1952 film Viva Zapata!, in which the Morelos revolutionary is played by Marlon Brando. Early on in the film a citified radical intellectual – played by Joseph Wiseman – comes to the rebel lines and calls Zapata’s name. After being almost shot by trigger-happy militiamen, he is admitted to Zapata’s headquarters, there to leaven an inarticulate movement of the soil with doses of sophisticated Marxism.

This is not to imply that Zapata himself was some lummox who let himself be led astray by a group of leftist eggheads. Though barely literate, Zapata resembled Pancho Villa in being a man who combined a lack of formal education with a high degree of native intelligence.

The citified radicals were welcomed not because Zapata was fooled by their slick talk, but because he instinctively knew that it was these men who best articulated his own views. Still, people tended to smile when manifestos and communiqués came out over Zapata’s name that contained references to Nero, Agrippina, and Louis XIV.

These were mainly the handiwork of Antonio Díaz Soto y Gama. A militant anarchist and fiery orator, he was the most colorful of the urban intellectuals who joined Zapata. Soto y Gama once figured in a farcical controversy with Alvaro Obregón in the Mexican Congress.

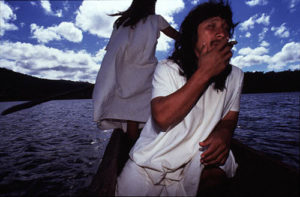

Love for the Indian is a yardstick of revolutionary commitment and Soto y Gama claimed that when the revolution broke out, he had headed for the hills and lived like an Indian. Thundered Obregón: “Sr. Soto y Gama should know that he is talking to a pure Mayo Indian, one who knows their language and can make speeches in it.” Obregón’s Indian affiliation was more sentimental and rhetorical than ethnic. He had lived among the Mayos, he knew their language, he fought for their rights, but he was actually descended from a family whose original name was O’Brien.

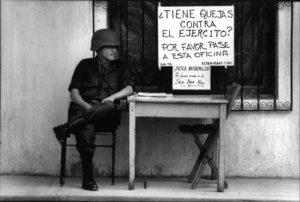

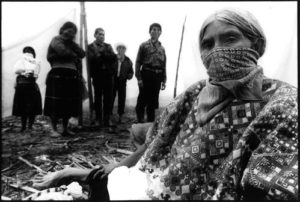

Putting leaders aside for a moment, there are amazing similarities between the Zapatista movement of the teens and its successor of the nineties. Both flourished in a State with high mountains, great natural riches, and an exploited underclass that benefited little from this wealth. Both Zapatista regions – Morelos and Chiapas – had an entrenched economic oligarchy that violently resisted attempts at reform.

In Morelos it was the owners of sugar cane plantations. In Chiapas it is the cattle raisers. In both cases Mexico has presidents who considered themselves progressives but were condemned by the Zapatistas as prophets of too little and too late. Just as Zapata became the first rebel to take the field against Madero, so did Marcos against Salinas de Gortari.

Another interesting similarity involves limits of power. Where Zapata was militarily invincible in his Morelos fiefdom, where he knew every tree and rock, he was unable to extend his authority outside this relatively small area. Marcos today is master of large parts of Chiapas. Yet, if fighting were to resume, it is highly unlikely that he could break out of his heartland in the Lacandon sierra.

Returning to individual leaders, Zapata was an uneducated but intelligent chieftain who has the wisdom to import a brain trust to guide him in areas where he was uninformed. Marcos, who is both intelligent and educated, functions as his own brain trust.