The brassy blast of a trumpet rips me from the comforting embrace of Morpheus. As the familiar strains of Las Mañanitas register in the fuzzy workings of my brain, I roll over and open one eye to peer at the clock. It’s 4:30 a.m. Ah, yes. ¡Feliz Día de las Madres!

I patter over to the window, looking out towards the street to find the protagonists of my startled awakening. A street light outside my neighbors’ entrance illuminates a dozen musicians decked out in matching uniforms standing in the bed of a battered pick-up truck. They are belting out the unmistakable melody that will be played in salute to millions of Mexican moms on this day.

Moments later Doña Carmen, matriarch of the family next door, slips out of the gate, a long rebozo wrapped around her shoulders to fend off the chilly pre-dawn air. Following behind comes a sizable brood — at least a half dozen grown off-spring who have pooled resources to spring for this middle-of-the-night serenade, plus their own children and grandchildren. They all huddle on the curb, applauding as the band pauses before launching into the next number, a rousing rendition of the ranchero love song Paloma Querida (Beloved Dove).

The tune-fest continues with “El Brindis del Bohemio” (The Toast of a Bohemian) and a few other ditties of similar word and feeling. The musicians suddenly hunker down in the back of the truck, clutching their instruments firmly as the driver roars off into the darkness. The band has a long list of appointments to keep on what for them will be a busy and lucrative work day. Doña Carmen and her clan laugh and chatter as they disappear once again behind the iron gate.

Once upon a time I puzzled at why any mother would take delight in being roused from sleep at such an ungodly hour. I have since come to appreciate the beauty and romanticism of the traditional serenade known as ” el gallo” (the rooster) or “mañanitas” (little mornings). For generations of Mexicanos this has been a fundamental tool for courting and feting women. It’s just part of the emotional landscape in a country distinguished by its warm, demonstrative people.

With vicarious pleasures of the sidewalk concert cut short, I retreat to the bed, snuggle under the covers and quickly doze off. But my regained slumber is short-lived. At 6 a.m. a barrage of sky rockets rents the air. The blasts are loud enough to wake to the dead, which in fact has something to do with their intent. They are being fired off to announce the sunrise Mass that is about to start at the village cemetery, a traditional and always well-attended service in remembrance of mothers who have passed on to greener fields.

Resigned now the inevitability of an early rising, I fluff up the pillows to enjoy a little quiet time dedicated to pleasure reading. Like other moms in Mexico, this one day out of the year I can be comfortable with some self-indulgence and well-earned pampering. A little later I hear my own youngsters rattling around on the ground floor and catch the enticing aromas of fresh-brewed coffee and bacon wafting up from the kitchen. Oh, joy. Happy Mother’s Day!

The earliest celebrations of Mother’s Day in Mexico are said to date back to the 1920’s, having been inspired by the United States holiday originated in 1906 by Anna Jarvis. While families in the U.S. and some other countries honor mothers on the second Sunday in May, the day set aside for ” madres mexicanas” invariably falls on May 10.

Mother’s Day has no official designation on either the civic or liturgical calendar, yet it probably qualifies as the most widely and fervently celebrated of all Mexican holidays, ” la madre de las fiestas,” as one modern writer on the topic so rightly puts it. Since May 10 so often falls on a weekday, patterns of everyday life may be disrupted. Government agencies and many other employers usually grant working moms a day off from their jobs. Progeny blow off regular business in favor of tasks related to regaling their mothers. It’s accepted behavior. No one questions, no one minds.

Not long after I came to Mexico — before I had some grasp on deep nuances of the culture, before I became a mother myself — I made the mistake of trying to do some business in Guadalajara on May 10. I prudently called in advance to see if the immigration office would be open that day. “Of course we’re open,” an anonymous official assured me. When I arrived I found the doors to the office open, but inside the desks and chairs normally occupied by female agents (including the one I was desperate to see) were all ominously vacant. The man at the registration desk shrugged his shoulders apologetically. “Sorry,” he said, “They got the day off.” My next stop, at the telephone company’s main office, brought a greater surprise. Affixed to the locked entrance was a terse sign reading: “Closed for Mother’s Day.” Not so much as a hint of contrition from Ma-Bell de México. It was a defining moment in my growing comprehension of just how big a deal this unofficial holiday is.

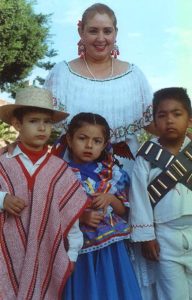

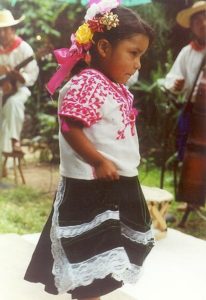

For mothers of school-age children, Día de las Madres brings colorful festivals in which teachers and their pupils present diligently-rehearsed talent shows. The heart and soul put into these productions is palpable. When offered with genuine affection, there’s nothing quite as endearing as a group of kindergartners reciting a saccharine choral poem in perfect unison or a troupe of gawky adolescents costumed in swirling skirts and charro outfits pounding out the lively steps of the emblematic folk dance called the Jarabe Tapatio.

On the home front, 10 de Mayo means Mamá will probably get relief from the daily drudgery of household chores. Families who can afford it are likely to wine and dine her at a nice restaurant. Those of lesser means pitch in to prepare a home-cooked “comida” featuring Mom’s favorite dishes. Big family get-togethers honoring two or three generations of mothers are widely popular in all social strata.

The occasion also calls for special gifts. Fresh flowers are so readily available and affordable that some sort of floral tribute for Mamá is practically de rigueur, be it a single, gorgeous blossom plucked from the garden, a simple bouquet of roses or gladiola, or an extravagant multi-colored arrangement. Other tokens of affection may be practical items selected to ease mother’s job as a housewife — new dishes, glassware, kitchen gadgets or a major appliances such as a washing machine, refrigerator, stove, or microwave oven. She may also receive clothing, fashion accessories, outright luxuries such as jewelry and perfume or even that now essential tool of every 21st century woman–a new cel phone.

What counts here are not the material goods, but their invisible wrapping–genuine love and appreciation for the person regarded as the pillar of the Mexican family. She is viewed as the symbol of unconditional love and solidarity, the ever comprehending, protective, self-sacrificing glue that binds the family unit.

In a recent survey conducted among mothers in Mexico City — where the rate of family disintegration is likely highest in the nation — 62 per cent of those interviewed confessed that anticipation of Día de la Madres prompts sentiments of joy and pleasure, 71 per cent said that they considered spending the day at home with the family the ideal way to mark the occasion, and 23 per cent cited “love and affection” as the best of all possible gifts.

Although the role of women in Mexican society today is shifting decidedly, the ideal of “la mujer abnegada” and reverence of motherhood remain deeply ingrained in the collective consciousness. They are concepts that have been constantly reinforced in popular music, literature, films and television soap operas.

In 1959, not long after the celebration of Día de las Madres became solidified, the first edition of an elementary school reader entitled “Mis Primers Letras” went into publication. The book’s prevalence in the Mexican classroom, even today, puts its on a par with the U.S. classic “Fun with Dick and Jane.” Unit three contains a reading exercise, penned by Carmen G. Basurto, that exemplifies filial devotion. Its few simple words have become burnished in the minds of millions of sons and daughters, my own included. Its recitation on the 10th of May is a fail-safe tactic to wrench a mother’s heart and bring tears to her eyes, yes, my own included.

“Mamacita”

Mamacita de mi vida,

mamacita de mi amor,

a tu lado yo no siento

ni tristeza ni temor.

Mamacita, tú me besas

sin engaños, sin rencor,

y por eso yo te quiero,

mamacita de mi amor.