For an unusual winter break, how about a Mexican train ride? The Reader’s Digest called Mexico’s famous Copper Canyon railroad trip, “the most dramatic train ride in the western hemisphere”. Even that description fails to do justice to the spectacular scenery and sightseeing along the line.

The railroad was originally built to give southern Texas farm produce access to a Pacific port. It is still the only major transport link across the Western Sierra Madre for a very long way in any direction, though a paved road will soon open this area up like never before!

The line runs from Ojinaga on the Texas-Mexico border to Chihuahua and then west through canyon country to the Pacific port of Topolobampo, near Los Mochis. The railroad’s construction ran into all kinds of problems – from the opening of the competitive Panama canal route, to the Mexican Revolution (which began in 1910), but the greatest obstacle was the apparently untameable Sierra.

IMPOSSIBLE?

The initial capital was mostly American but both the investors and their hired engineers gave up the project in the first half of this century, pronouncing it “impossible”. After nationalizing all foreign-owned railroad lines, Mexico announced, in 1953, plans to complete the Copper Canyon line which at the time still lacked a route through the most difficult part of the mountain range, near Temoris.

Eight years later, the line was finished. It had involved some extraordinary engineering and the final cost was over US$100 million. The highlights include the elegant La Laja canyon bridge, which comes immediately after a tunnel at km 638, a complete 360 degree loop at El Lazo, km 585 (there are only three comparable examples anywhere in North America) and a 180 degree turn inside a tunnel near Temoris at km 708. Incidentally, the kilometre numbers for the entire line are taken from the eastern terminus at Ojinaga.

Between Chihuahua and Los Mochis, the section usually travelled by tourists, there are 37 bridges and 86 tunnels; most of them are between Los Mochis and Creel. The line crosses the Continental Divide three times, reaches a maximum height of 2400 m, and for much of its route skirts the rim of an enormous canyon system.

BIGGER THAN THE GRAND CANYON

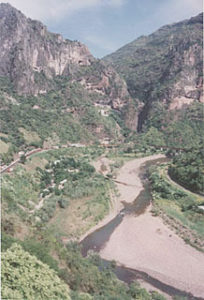

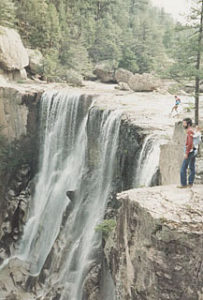

This canyon system is what gives the railway its name. Strictly speaking, the Copper Canyon is only one of a number of interlocking canyons or barrancas in the area. Not only are these barrancas deeper and narrower than the U.S. Grand Canyon, they are also longer. Whereas the Grand Canyon is desert-like, with virtually no vegetation, the Copper Canyon is thickly wooded in most places and a beautiful green, especially in the rainy season from June to October.

START FROM LOS MOCHIS

Whatever the time of the year, it is best to begin from Los Mochis at the western end of the line. This more or less guarantees seeing the best scenery of the route in daylight, even if the train should be delayed (which, happily, these days is rare!). Starting from Chihuahua, any unforeseen delay may mean you reach the most scenic part just as the sun is disappearing below the towering canyon walls – perhaps only minutes too late for good photographs of the most exciting and awe-inspiring part of the whole journey.

STAY OVERNIGHT

About half the passengers travelling this line stop overnight somewhere in canyon-country. Most select Creel, the biggest town between Chihuahua and Los Mochis, named for a former Governor of Chihuahua who was vice-President of the Kansas City, Mexico and Orient Railroad, the company which started building the “Copper Canyon” line.

But Creel is not really very close to the canyons. The scenery around Creel is attractive but nowhere near as spectacular as it is around Divisadero, the viewpoint where the daily trains each way stop for a few minutes to allow travellers to disembark and take photos.

SUPERB LODGING

Five minutes by train west of Divisadero (ie towards Los Mochis) are three hotels, two of which are excellent. All are reached from “Barrancas” station, not from “Divisadero” station.

The “Posada Barrancas” and the “Posada on the Rim” are operated by the Balderrama chain which includes the luxury Santa Anita in Los Mochis, and the Mission in the small village of Cerrocahui, near Urique. The Posada Barrancas, set back a few hundred metres from the rim, is clean and comfortable, but lacks character. The superior Posada on the Rim is built, literally, overhanging the near-vertical canyon wall.

A few minutes walk from the station is another absolutely outstanding hotel – the Mansion Tarahumara – which is still undiscovered by the vast majority of tourists. Its guest rooms are enchanting Hansel-and-Gretel-style stone cottages dispersed in a veritable botanical paradise. Rates here include three imaginative and delicious home-cooked meals. A mural on one side of the imposing dining-hall depicts the history of the Raramuri tribe (“lightfooted people”) as the local Tarahumara Indians call themselves. This lightfootedness refers to their legendary speed and endurance in long-distance running races where opposing teams compete to kick a wooden ball from one hillside to the next.

From the top of the ridge above the hotel, you are surprised by one of the most breathtaking panoramas in North America. The view is yours to contemplate and admire as long as you like, secure in the knowledge that despite the extreme ruggedness of this vast wilderness, a comfortable, welcoming hotel is nearby.

A rocky path leading down from the rim ends at a typical Tarahumara dwelling – a cave in the canyonside, with a natural spring as its running water supply and an open-air kitchen and dining-room. The local Indians will, shyly, offer you small baskets and hand-made dolls as souvenirs.

So, this winter, why not plan an escape to Mexico’s fabulous Copper Canyon?

Tony Burton, the writer of this article, won an international travel-writing competition for an article about the Copper Canyon in 1991.