Arts of Mexico

At least ten years before the “Big Three” – Rivera, Orozco, Siqueiros – came into their own as world-renown muralists, a lone painter was setting the groundwork. His name was Saturnino Herran. He was the first Mexican artist to envision the concept of a totally Mexican art. And he laid the foundation for the development of the muralist movement.

In a catalogue dedicated to Herran’s work published in 1997, Carlos Fuentes, the novelist, described the painter as the one who opened the way not only for the muralists but for all the nationalists who contributed so much to give the Mexican people a conscience of whom they are and who they could be.

Although he had a number of critics in his time, his work has stood the test of time. Today it is well-accepted that Saturnino Herran was an extraordinary draughtsman and painter who was the first to bridge the gap between Mexico’s two cultures – pre-Columbian and Hispanic.

Herran was born in Aguascalientes on July 9, 1887. He was the only child of a Mexican father and a French Swiss mother. His father owned the only bookstore in the city and was a professor of bookkeeping at the Academy of Sciences.

The young Herran showed early talent and in 1897, at the age of 10, was given private drawing lessons in his native city. In 1901 he entered the Aguascalientes Academy of Sciences and took drawing and painting classes from Jose Ines Tovilla and Severo Amador.

In 1903 the family moved to Mexico City where, unfortunately, the painter’s father died soon after. That left Herran as the sole support of himself and his mother. He managed to get a job in a telegraph office during the day but studied art at night under Julio Ruelas at the San Carlos Academy. Soon after, he received a scholarship which permitted him to study painting full-time.

At the academy, Herran studied drawing under Antonio Fabres, a Catalan painter, and painting under German Gedovius. From Fabres, a brilliant draughtsman, he learned composition and the theories of European Modern Art. Under Gedovius, who was an exceptional colorist, he developed his own excellent eye for color.

During his education at the academy, the teaching was based on the European model of art, which revered the Greek and Roman sense of aesthetics. It saw Mexican art as the work of a semi-barbarous people. Having studied under Ruelas, Fabres, and Gedovicius, Herran could have emerged as a great painter in the academic tradition, but he was looking for something deeper, more spiritual.

Though he did embrace the contemporary European influences that he was being taught, he, at the same time, he immersed himself in the artwork of his own culture – the indigenous people. The native artwork of his country along with the work of Frank Brangwyn, a British muralist whose work he saw in art magazines, influenced greatly the type of work he was to produce and the venue he chose in the years to come.

By 1908 his work was already being recognized, and he received several awards. In 1909, he became a professor of drawing at the academy. The next year he was offered a scholarship to study in Europe but had to reject it as he couldn’t leave his mother with no means of support. Aside from his teaching, he was paid by the National Museum to sketch the Teotihuacan murals, which had just been discovered in the previous century.

The real turning point in his career came in 1910 on the Centennial Anniversary of Mexico’s Independence Day. There was to be an exhibition of Spanish painting but no exhibition of Mexican art. Herran along with Orozco formed the Society of Mexican Painters and Sculptors and staged a counter-exhibition with their own work. It included a triptych Herran had done called “Legend of the Volcanoes”, a parable about an Indian Prince and a European princess. It wasn’t a great work, but it reflected his wish to assimilate Mexican history into the country’s art.

The exhibition was so popular that the entrance had to be controlled by the police. It made an impression on Jose Vasconcelos who was to become the Secretary of Education in the new Mexico after the revolution. He recognized at that moment that murals could reach a wide audience and that painting wasn’t only for the elite.

Herran was among the first artists Vasconcelos commissioned to do mural paintings, and in 1911 he completed his first large-scale mural in the School of Arts and Crafts. His work served as a model for the many large scale murals that were to be later commissioned in the 1920s and 1930s.

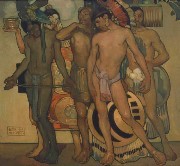

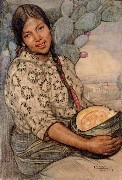

Saturnino Herran’s work was not so much a break with tradition as a gentle transition to a whole new awareness and identity. Mexico was a mixed-race society which embodied two ways of looking at the world. With consummate skill, he gave tangible form to that symbiosis. He did majestic paintings of Mexican Indians, giving them heroic strength and dignity and explored the contemporary realities of Mexico with a dose of social realism. He experimented with new perspective and compositions in a desire to capture the inherent beauty of his countrymen. He was sensitive to indigenous beauty and caught the natural expression of his subjects.

His work was part of a movement called “syntheticism” of which he was the best representative. It was marked by its tendency to simplify and introduced not only new forms of expression but also new subject matter in dealing with Mexican life.

His detractors accused him of being mannerist and judged his art as effeminate, but his work has held up over time.

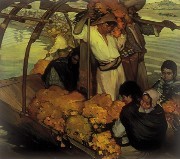

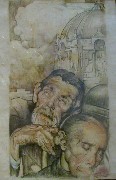

In 1914, with his career in full swing, he married Rosario Arellano with whom he had one son, Jose Francisco. That year he began painting his famous watercolors consisting of colored pencil sketches filled-in with watercolor. He also started his last mural, a triptych entitled “Our Gods”, and following year initiated a series called “Mestizo”, in which he pays tribute to the beauty of the mixed race of his people.

He was never to finish “Our Gods”. He worked on it for four years until his death in 1918 from a stomach ailment.. The unfinished triptych still exists in several sections. It’s considered a masterpiece and can be in the National Theater in Mexico City.

His obituary filled the front page of the newspaper, El Pueblo. His name was the only headline. Even at the time of his death, Herran’s contribution to Mexican art was understood by his fellow countrymen. His good friend and the poet, Ramon Lopez Velarde, wrote Oracion Funebre, a prayer for Herran. He read it a year after the painter’s untimely death at the Escuela National Peparatoria. It’s rare for the common people in a country to mourn an artist’s death but such was Herran’s impact on the lives of his fellow Mexicans.

Though he died at 31 years old, his legacy is solid. He mixed classicism with modern art and executed this background through a Mexican sensibility. He understood the soul of his people, and he captured it masterfully.

As the author of Siqueiros, Biography of a Revolutionary Artist and a historian, I greatly appreciated this tribute to Saturnino Herran, certainly one of the important precursors of the mural movement and modern Mexican culture. Thanks Mexican Connect for this and other gems from Mexico.

Dear Dr. White, Such very kind words from an esteemed academic are very much appreciated! Thank you. TB.