Arts of Mexico

Manual Alvarez Bravo was one of the truly great photographers of the twentieth century. His work sprang from a vision born of his time and his culture, but it touched people from every society all over the world. Diego Rivera called his work a profound and discrete poetry. He said it was like those particles suspended in the air that render visible a ray of light as it penetrates a dark room.

I first saw Alvarez Bravo’s work in a book of photographs put together in the 1950s by Edward Steichen, then the curator of the New York Museum of Modern Art, called The Family of Man. It was a moving book, which spurred my life long interest in photography as an art form.

It was also the rightful home for work of Alvarez Bravo’s caliber and sensibility. His work is imbued with a heightened awareness of the everyday. Its sense of fleeting time reminds us all of our fragility and connects us in a common bond. It has a quiet humility that comes with the knowledge that the “other” is us.

I met Alvarez Bravo in the late 1960s in Mexico City. I was struck by how much of the man comes through in his work — his gentle nature, his alert and curious mind, and his subtle humor and quick intelligence. At the time, he was living with his third wife, French photographer, Colette Alvarez-Urbajtel. It is a testimony of his commitment to the medium that all three of his wives were or became photographers in their own right.

Manuel Alvarez Bravo died on October 19, 2002, 100 hundred years after his birth, having lived through the most tumultuous period of Mexico’s history — a history that molded his vision and stirred his creativity. “I am content with my country: good, bad, and worse than bad,” he was to have said. “I am enchanted by my country.”

He was born February 4,1902 and raised in “an atmosphere in which art could breathe”. His father, though a teacher by profession, actively pursued painting, photography, and writing, and was the author of several produced plays. His grandfather was a professional portraitist.

He was 8 years old when the revolution began. It left vivid memories. From his classroom he could hear gunfire, and often while playing after school, he would come upon the bodies of the dead. Death played an important role in his photographs. Sometimes it is explicit as in his photograph of the “Striking Worker, Assasinated”, but more often it is implied as in his photograph entitled “Portrait of the Eternal”. In a subtler form it is present in his everyday photos that are an affirmation of life.

Alvarez Bravo had to leave school at 13 years of age. He first worked as a clerk for a French company and then for the Mexican Treasury Department, studying accounting in the evening, but his calling was elsewhere. The following year he attended night classes at the San Carlos Academy in literature, painting, and music.

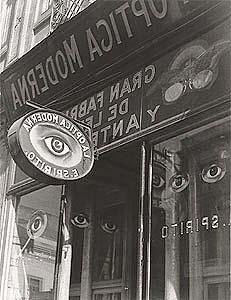

His love of literature was later to express itself in the interesting tongue-in-cheek titles that he gave his work, a good example being “Optical Parable.” “The worst thing you can do,” he said,“ is title a photograph ‘untitled’ because then it has no differentiation from any other picture.” Music, he said, also influenced his work, especially Bach and the Italian Baroque.

He possessed two books which were to influence his early photographs. One was on Picasso and the other on Japanese prints. The former encouraged him to experiment with cubistic abstract composition as in “Paper Games,” an interest that was short lived. The latter contained the prints of Hokusai, whose influence can be seen in his early Mexican landscapes.

His first foray into photography was under the tutelage of Hugo Brehme, German photographer, whom he met in 1923. In 1924, he bought his first camera and with initial advice from Brehme and subscriptions to various American photography magazines, his work in photography began. The years that followed were a time of experimentation, and in 1926 he won first prize in a regional photo exhibition.

However, in 1927 a major shift in his perception took place that was to profoundly affect his work. He met the photographer and former lover of Edward Weston, Tina Modotti, who influenced his work (he later destroyed his earlier prints) and introduced him to the thriving intellectual and cultural environment of Mexico City. On Modotti’s suggestion, he sent Weston several of his photographs. An enthusiastic Weston wrote him words of encouragement. Shortly after, he was to become a major figure in the Mexican art movement.

In 1930, Alvarez Bravo quit his job with the government to become a fulltime freelance photographer. When Tina Modotti was deported for political activities, she left him her camera and her job at Mexican Folkways magazine. It was for Mexican Folkways that he started photographing the work of the Muralists – Rivera, Siqueiros, Orozco – as well as many of the other great painters of the times.

The 1930s were productive years for Alvarez Bravo. He turned away from his early European influence and found his Mexican voice. His photographs become more complicated. The ancient symbols of blood, death, and religion start to appear in his work. He now deals with the paradoxes and ambiguities of his culture.

A dreamlike quality becomes evident. In “The Daydream,” photographed in 1931, a young girl stands on a balcony caught in a wistful moment. It conveys a message across time and space that is to appear more and more often in his work The photographs from this period become metaphorical and evoke the lessons of parable or fables. The titles of his photographs are often based on Mexican myth and culture.

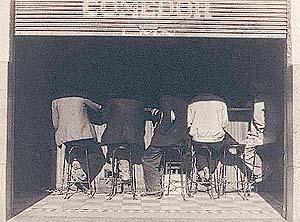

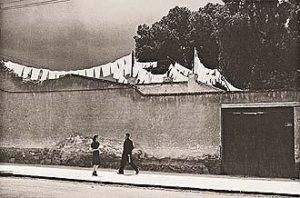

Urban streets, shop windows jammed with goods, vignettes from life’s on-going little dramas become the subject of his photographs. He uses a large camera, which provides more detail in the finished print and is suited to his style. His photos are deliberate, intellectual, and thoughtful.

In those years he met two of the world’s greatest photographers – Paul Strand and Cartier-Bresson – both of whom admired his work. He introduced Strand to Mexico, and they worked briefly together. With Cartier-Bresson he shared an enthusiasm for the mysterious imagery that was created when animate elements were juxtaposed against the inanimate, a relationship most often found in urban settings.

In 1938, he met the Surrealist Andre Breton through Diego Rivera. Breton was taken with his work. He reported back to a French avant-garde magazine, “Never before has reality fulfilled with such splendor, the promises of dreams.” When Breton returned to Paris, he included Alvarez Bravo’s work in an exhibit he organized, and the next year chose his pictures for an international Surrealist exhibition in Mexico City.

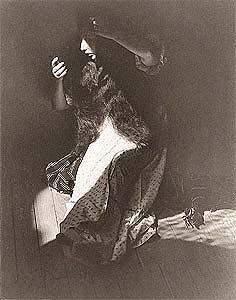

Breton commissioned Alvarez Bravo for the cover of the catalog, but the censors rejected it. Mexico wasn’t ready for a mostly naked woman wrapped in bandages accompanied by a prickly cactus. The implication was too suggestive. So was the prominent display of pubic hair standing out against the bandages. Though “The Good Reputation Sleeping” never made it into that exhibition, it’s been shown in many since.

Surrealism, however, was too limiting for Alvarez Bravo. It had no relationship to his Mexico with its many layers of meaning and sources of influence. He was a man of his time caught up in Mexico’s search for its identity. Yet, he wasn’t a political man. He always maintained a certain detachment, and his commitment was to human enlightenment.

Through most of the 1940s and 1950s, he was involved with teaching and photographing for the film industry. In 1959 he changed course and become one of the founders of Fondo Editorial de la Plástica Mexicana, a publishing house that produces very fine books on Mexican art. He did little personal work through much of that period, and the world seemed to forget him.

However, starting in the Seventies, his well-deserved but late-coming recognition finally caught up with him. Major exhibitions of his work were held in Mexico and elsewhere, which introduced a whole new generation to his work. These shows established him as one of the foremost masters of modern photography. Many prestigious awards as well as several edited portfolios of his work followed.

Manual Alvarez Bravo remained a photographer to his last days. When he could no longer move about easily, he photographed nudes. “It wasn’t the sort of work one can complain about,” he said. But he missed the countryside and the daily life of the street.

He never considered himself a craftsman and the quality of his prints was never a primary consideration. The everyday people of his homeland were. These were the people he believed he was photographing for. But he was a superb composer, and his compositions with their poetic images touch the sensibilities of all people. His longtime friend, Octavio Paz, described Alvarez Bravo’s photographs as instants of revelation, not stories… realities in rotation, momentary fixities, on the brink of disappearing.

Books on Manuel Bravo

- Manuel Alvarez Bravo: Nudes: The Blue House:

by Manual Alvarez Bravo (photographer)

Available from Amazon Books: Paperback - Manuel Alvarez Bravo

by Susan Kismaric 1997 - Manuel Alvarez Bravo: Photographs and Memories

By Federick Kaufman 1997 (paperback)

Available from Amazon Books: Paperback - A song of Reality: Latin American Photography 1860 – 1993

by Erika Billeter 1998

Available from Amazon Books: Hardcover - Manuel Alvarez Bravo: Photographs from the J. Paul Getty Museum

By J. Paul Getty Museum 2001 (paperback)

Available from Amazon Books: Paperback - Manuel Alvarez Bravo

by Amanda Hopkinson 2002 (paperback)

Available from Amazon Books: Paperback - M. Alvarez Bravo

by Manuel Alvarez Bravo (limited availability)

Available from Amazon Books: Paperback