A Voice from Oaxaca

Tejate is a pre-Hispanic corn and cacao based drink. It is likely the only complex food recipe in all Mexico still enjoyed today just as it was thousands of years ago in Oaxaca.

When visiting a Oaxacan marketplace and enjoying a half jícara gourd of tejate, you’re likely treating yourself to the same carefully crafted beverage, made with virtually the same ingredients and preparation methods as was the case 4,000 years ago.

For those who have never tried or recognized tejate in the markets, it’s the foamy beige drink ladled out of oversized green glazed clay tubs, worked and served exclusively by women standing behind a table, in a stand or a small stall.

Oaxaca is the south central Mexico UNESCO World Heritage Site noted for its colonial architecture, Dominican churches, museums and galleries. Oaxaca’s many diverse indigenous cultures and nearby ecotourism preserves, craft villages, mezcal production, as well as Zapotec and Mixtec ruins invite the visitor to linger a while. And its gastronomic greatness is arguably unrivalled in the country.

Despite the fact that Oaxaca is a tourist mecca, rarely do visitors — or for that matter, residents — have the opportunity to witness how tejate is made from start to finish. And yet, while other similar drinks do exist, tejate is a uniquely Oaxacan beverage deserving of widespread acclaim. Learning the process today provides a glimpse and better understanding into tejate’s past. Anecdotal evidence as well as that from the social and physical sciences provide a helpful starting point.

The pre-Hispanic origins of tejate

All of the key ingredients in tejate are native to Mexico, and in fact to the state of Oaxaca except for one. Cacao comes from the state of Chiapas, and some cacao is now imported from Tabasco. This fact immediately distinguishes the drink from other noteworthy prepared Oaxacan foods, such as some of its moles.

Many mole ingredients were first brought to Mexico by the Spanish. Thus, we cannot trace, for example, the highly complex mole negro with its 30 to 35 ingredients, to pre-Hispanic times. By contrast, tejate today is likely the exact same beverage that was ceremoniously drunk by the Aztecs in the 1400s and, for thousands of years before them, by the Zapotecs who were, and continue to be the predominant ethnic group in Oaxaca’s central valleys and further beyond.

The tools of the trade and means of production employed in 2012 AD are, on balanc,e the same as those used in 1012 BC — rock, fire and clay. Admittedly, not all of the metates used today are the large smooth river rock grinding stones utilized generations ago. In fact, commercial manufacture of tejate often includes taking some of the ingredients to a local molino for milling. But witnessing the labor intensive transformation of raw material into tejate conjures clear images of ancestral production.

The Spanish arrived in Oaxaca in 1521. Their first contact was with the Aztecs. Early European writings based on interaction with the indigenous group document the use of corn and cacao and some of the other ingredients used today, as well as the process of making the drink frothy. They also confirm that the drink was reserved for the upper classes, likely royalty. We also know that the Aztecs traded jícara gourds, a traditional drinking receptacle, and cacao.

But that only takes us as far back as the most recent pre-Hispanic era.

Other evidence confirms that up to 4,000 years ago there were trade routes between Oaxaca and the coastal regions further south, such as Chiapas, where cacao has grown since time immemorial.

Physical evidence includes residue found in clay pots dating up to 2,500 years ago and containing a compound found only in cacao, suggesting that cacao was then being cooked by Zapotec residents of Oaxaca.

Perhaps the most compelling evidence is contained on a vase decorated with painted imagery and dating to about 1,300 years ago. On the “Princeton Vase,” one encounters what the experts presume is a prepared cacao-based beverage being poured from high into a vessel below, the aeration creating the foam. The dress and composure of the individuals depicted suggest the drink was ceremoniously imbibed by royalty.

Today, the same process plays out, but by indigenous village vendors — far from royalty, yet highly respected for their culinary craft by those in the know.

Part of the foregoing is a summary of the compilation of evidence contained in Tejate: Theobroma Cacao and T. Bicolor in a Traditional Beverage from Oaxaca, Mexico, by Daniela Soleri and David A. Cleveland.

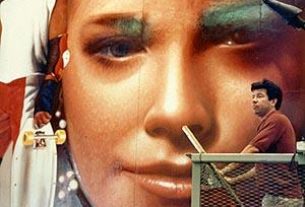

Gloria Cruz prepares tejate in a Oaxaca village

Gloria Cruz holds a jícara high above her head. She deliberately allows its liquid to fall in a controlled fashion back into the giant green-glazed ceramic tub from which it was taken. She continuously repeats the process, each time attentively checking the progress of the froth as it builds with each subsequent pour.

It’s 10 a.m., Sunday morning at the Tlacolula market. Gloria has just finished setting up her stand and unpacking several kilos of beige corn masa, which she has brought from her homestead in nearby San Marcos Tlapazola. San Marcos is a traditional Zapotec village with about 1,500 residents, known mainly for not tejate, but rather its handcrafted red clay pottery.

Mixing water into the masa, then ceremoniously creating the frothy topping, is the final step in preparing tejate for sale to passersby — residents of Oaxaca and nearby towns and villages who have come to Tlacolula to shop, other market vendors, and the odd tourist who is familiar with the beverage’s nutritional properties, richness and nutty (almost mocha-chino) flavor.

Gloria awoke at 3 a.m., as she does most Sundays, to begin making her day’s quantity of masa to then turn into tejate. When she has time for some pre-preparation the night before, she sleeps in until 4.

Gloria had purchased all the ingredients she would need in the same market the week before,except for corn on hand from her own harvest. Aside from occasionally buying maize, she buys red cacao (already fermented and toasted), seeds of the mamey fruit, lime mineral, pecans or peanuts (depending on the season) and Quararibea funebris (the flower of an aromatic bush, often referred to as funeral tree flowers, or rosita de cacao, although it is not related to cacao). Ash from cooking tortillas or firing pottery is always on hand.

Gloria places one fourth kilogram of rositas, six mamey seeds and one fourth kilogram of cacao on a comal, or griddle. She toasts these ingredients on top of a flame, using dried agave leaves as fuel. She does the same with one eighth kilogram of raw peanuts. The toasted peanuts and the first mixture (pixle) are kept separate, each in its own clay bowl.

Using a clay colander, Gloria then washes four kilos of raw corn kernels, making sure to pick out any small stones. She puts spring water into a large clay cauldron sitting on top of the flame, rejuvenating it with the addition of more dried agave leaves. She adds a small amount of powdered lime. She then strains three kilos of ash, places it in the pot, then adds the corn. More agave leaves added to the flame helps to bring back to a boil. Regular stirring prevents sticking.

By now, Gloria’s sister-in-law María has awakened. From this point on, she will help will the further preparation of the masa, and with breakfast.

At about 5 a.m. it’s time for hot chocolate and sweet rolls, while the corn continues to cook. After about 40 minutes, the flame has died out. The boiled corn is once again strained, this time to cool it and to remove excess ash. Gloria’s recipe calls for only a little sweetness, which the ash provides. The two women clean every pot and utensil immediately after use.

It’s still dark out. María and Gloria walk seven blocks to the mill, over a muddy potholed road, corn and pixle in hand. They knock on the door of the molino and wait. After a few minutes, a woman appears, welcomes them in, and turns on the light. She washes down the machinery, then weighs their two containers. She then mills the pixle into a masa, María and Gloria assisting with each step. The smell of cacao fills the molino, then the maple-y aroma of the rosita overtakes all, that same scent one occasionally encounters when driving along secondary highways and dirt roads in rural Oaxaca. Next, the corn. The miller knows exactly how much water to add to the corn as it goes through the apparatus in order to provide the white masa with optimum consistency.

It’s 5:50 a.m., and the walk back to the homestead is no different than it was arriving. It’s still dark. But by now one hears the sounds of roosters.

The masa blanca must cool before further processing.

María alternates between preparing breakfast and polishing a clay figure to ready for the brick kiln. Gloria pours mezcal. It’s still cold out, and the masa is not yet ready for mixing on the metate with the rest of the ingredients. Mezcal warms, but more importantly, is customary — at least in this household. Gloria gingerly pours water over four metates, then thoroughly scrubs each. The water is then used to irrigate nearby saplings and plants. She then grinds the peanuts, setting this third mixture aside. A little corn is ground and mixed in with it, just to ensure all the peanut has been removed. Nothing is wasted. The pixle masa is ground, this time on the metate, and then once again a bit of corn is used to ensure all the pixle has been recovered.

Everything has its order: tradition which has been repeated for generations. Before the age of the electric molino, the metate was used exclusively. Even today, smaller batches for household consumption of tejate are ground entirely on the metate.

Gloria and María both work at thoroughly blending the corn masa with the pixle and peanut mixtures. It takes an hour and a half.

The metates are again scoured. But this excess water has nutrients from the corn and other ingredients. It’s saved in pails and fed to the donkey and chickens.

While the women were grinding on the metates, Mariá’s daughter Lucina had awakened, dressed, showered and gone into the kitchen to finish making breakfast. It’s 7:40 a.m., time to sit down to a fuller meal than earlier in the morning — sopa de guías, tortillas and salsa, all prepared fresh, along with coffee and another ritual mezcal.

The now beige masa must be tested before leaving for the market to ensure sufficient cacao has been used to guarantee a healthy froth, the sign of a successful tejate. Gloria mixes up a sample; a subtle smile of satisfaction emerges.

Gloria, María and Lucina walk along that same muddy road, now in the light of day, and await the arrival of a colectivo to take them to the Tlacolula market with their masa. They also have clay decorative figures and utilitarian vessels they’ve made throughout the week, to offer for sale.

The women arrive at the market at 9:30 a.m. They walk to their designated section of street, greet their fellow vendors from San Marcos Tlapazola and other nearby villages, and then walk to an indoor storage area. They carry back their tables, bottles of purified water, green glazed clay mixing vessels, tarpaulins, unsold red clay pottery from last Sunday, and everything else they need to begin preparing for sale.

By 10 a.m. Gloria and Lucina have erected the tarps. Lucina and María are now arranging their pottery while Gloria attends to the finishing touches of preparing her tejate.

While neither Zapotec royalty nor an Aztec queen, Gloria — smartly clad in her own colorful hand-embroidered traditional San Marcos Tlapazola garb — ceremoniously pours the liquid, arm stretched out and raised above her head, just as her ancestors did.

Gloria’s customers, mainly regular clients, begin to arrive just as the froth in the large green glazed clay pot takes on its tell-tale sign of readiness. She begins to serve her tejate, its consistency, flavor and overall appearance just as it was thousands of years ago. After all, the tools, their use and the ingredients have remained the same over millennia, long before the word Oaxaca had ever been spoken.