In those days a decree from Emperor Augustus was issued, ordering a census for the entire world. […] Everybody had to be registered, each one in his city. Also Joseph, who came from the lineage of David, came up from the city of Nazareth, in Galilee, to the city of David, named Bethlehem, in Judea, to register himself and his wife Mary, who was pregnant. Being there, the time for birth arrived, and she gave birth to her first born son; she wrapped him in nappies and put him in a crib, because they did not find a place in the inn.

Luke, 2:2-7

Soon we will enjoy our first Posadas for this year in Mexico.

Las Posadas are fiestas that begin on the 16th and end on the 24th of December. In Mexico, during this period, there are many Posadas every evening.

Invited -and as usual, some non invited- guests arrive at the house where the Posada will take place, always in the evening. A group goes outside the house, with lighted candles and papers with the words of the verses to ask for Posada. They sing,

En el nombre del Cielo

os pido posada,

pues no puede andar

mi esposa amada.

In the name of Heaven

I ask you for lodging,

because She cannot walk,

my beloved wife.

The group inside answers, also singing,

Aquí no es mesón;

sigan adelante.

Yo no puedo abrir,

no sea algún tunante.

This is no inn,

keep on going.

I won’t open the door,

in case you are a truant.

Many verses are sung in this fashion, with those outside asking for a place to spend the night and the people inside the house saying, no way, until those inside “discover” who are the personalities freezing outside. Then they open the door and let the pilgrims enter. In the very traditional Posadas, a girl is dressed as the Virgin Mary, while a boy represents Saint Joseph. In some cases even a burro is present, for the Virgin to mount. Sometimes, those outside carry images of the Holy persons with them.

When they open the door to let those outside enter, they sing,

Entren, Santos Peregrinos,

reciban este rincón;

no de esta pobre morada,

si no de mi corazón.

Enter, Holy Pilgrims,

accept this dwelling;

not of this humble house,

but of my heart.

During the rest of the party we break piñatas, there are villancicos -Christmas carols- in the air and we eat the traditional things: buñuelos (very thin fried pastries covered with sugar), colación (a mixture of different candies), tamales, and ponche, fruit punch.

This beautiful tradition of the Posadas comes from the times of the Colonial period, but it is interesting to note that before the Conquest the Aztecs celebrated every year the arrival of the god Huitzilopochtli, between the 7th and the 26th of December. Under the Spanish domination, Catholic priests incorporated some days of the ancient tradition to a new set of religious festivities.

One of those first Christian festivities in Mexico were Aguinaldo -Christmas presents- masses. After Holy Mass, piñatas were broken, people sang villancicos and they watched the performing of pastorelas. There were nacimientos (depictions of the birth of Jesus Christ) on display for everybody to visit and admire.

The Náhuatl people used to represent plays enacting important historical events and stories taken from real life. Missionaries incorporated this custom to the Christian holidays, so during the nine days of the Posadas many pastorelas were performed on stage. These pastorelas are dramatic pieces that represent the trip of Saint Joseph and the Virgin Mary to register themselves in the Roman census taking place in those days, or the hardships they suffered while looking in vain for lodging. The roles in these pastorelas included, besides Joseph and Mary, shepherds and shepherdesses ( pastores, hence the name, pastorelas), sheep, burros, and perhaps a little devil or two.

These pastorelas played an important part in the evangelization of the colonies. Franciscans and Augustines, among others, used these representations to accompany the religious activities of the day, making the festivities more attractive and colourful. As it was, this custom was preserved and is still cherished among the Mexican people, a people who love family traditions and vivid fiestas.

It is said that Marco Polo brought with him the idea of piñatas: vessels adorned with color paper, that in China, were broken by hitting them with sticks to commemorate Springtime. Italians adapted the action to symbolize the victory of Good over Evil. In Lent they made piñatas with seven colored paper points, each one representing a capital sin. The stick that broke these sins played the part of Christian faith.

In Mexico the piñata assumed this meaning and then some others. One of them: It is the devil that holds in his belly all that is good in this world, just as the olla inside the piñata is filled with fruit like mandarin, orange and sugar cane; candy and gifts. The stick (Christian faith), put to good use by the girl or boy who strikes at the piñata (the hard work of women and men in this world), breaks the treasure’s chest for the benefit of all.

The piñata is firmly tied to a rope, and then hung from a pole or the branch of a tree. Someone holds the other end of the rope, pulling the piñata up and down to make it a more elusive target. It is customary to let the youngest children start the hitting and then to give the opportunity to the grown-ups. The little ones will be able to see the moving piñata when they try to hit it, while the elders take their turn later, eyes covered with a handkerchief or shawl.

While the hitter is doing his or her best to break the piñata, people surrounding the action sing in a chorus,

Dale, dale, dale,

no pierdas el tino;

porque si lo pierdes,

pierdes el camino.

Hit it, hit it, hit it,

don’t lose aim;

because if you lose it,

you will lose your way.

Eventually someone, able or lucky enough to accomplish the task, will break the olla inside the piñata. Fruit, candy and gifts fall to the floor, for everybody to rush to gather whatever they can from the scattered goodies.

After piñatas, dinner is served. Tamales with atole, and crunchy buñuelos for desserts. Hot ponche will help to warm the cold winter evening. For the children, ponche made from seasonal fruits, like tejocote, guava, plum, mandarin, orange, or prune, sweetened with piloncillo (a brown sugar), and perfumed with cinnamon sticks or vanilla. For the grown-ups, the same ponche, but with piquete (sting), which is a bit of rum or tequila added to the potion to make it happier. There are as many ponche recipes as there are grannies in Mexico. In Colima, for instance, they prepare a delicious concoction made of milk, sugar, orange leaves and vanilla, grated coconut and a drop of rum.

When the Posada is about to end, every guest receives a small gift, or aguinaldo, usually a package containing cookies, dried and fresh fruit, and colación (assorted and colourful candies). Now is the time to sing villancicos, carols that talk about the good news given to the shepherds by the angels, that our Savior was born. A very old tradition calls for everybody to gather in front of the nacimiento (the nativity scene) to sing villancicos to the newborn child.

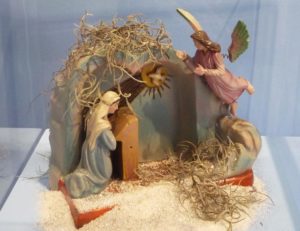

Traditional nacimientos picture the birth of Jesus. It seems than Saint Francis of Assisi was the first one to come out with the idea of representing with figures the scene in the stable of Bethlehem. That first nacimiento was placed inside a cave in Greccio, Italy, in 1223, to later become a well established tradition in that country.

The excellence of Mexican artisans helped in a significant way to the development of this custom in our country. A typical nacimiento shows Jesus in a crib, with the Virgin Mary and Saint Joseph at His side. Inside the portal (porch), which can take the form of a cave, a stone house or a cabin, there are several animals surrounding the Holy persons: burros, oxen, sheep, cows, horses. Additional personalities who take part are shepherds, angels, pilgrims, and the Kings from the East who came to adore Him. The star they followed to Bethlehem always crowns the nacimiento, giving it light and color.

Soon we will enjoy our first Posadas down here.

These traditions are alive and well in Mexico, thank God, in spite of the noise and hurried pace of our so called modern life.

This is a time for joy. This is a time for children. And as I watch them play and sing and have fun, I know I will remember my own childhood. I will remember those who are now gone, and I will think about the future.

Funny that events that occurred so many years ago bring us to think about the future. The only answer to this apparent paradox is, Hope. Hope in the future, hope in this Mexico that I love and which suffers so much. Hope in this world full of injustice, misery and pain. But a world that holds the promise of the Divine Child who wanted to come here to become one of us, to show us how precious human life is. To give us hope in ourselves.

And to teach us to live with yet another paradox: that the only way to save ourselves, is to think and act not on behalf of our own selves, but on behalf of those around us.

— Dumois. December, 1998.