Early one morning in late July, after being awakened by the infernal POP POP POP of today’s Mexican alarm clock, I arose reluctantly from the warmth of my bed, determined to find the true story of cohetes, the thundering skyrockets that blaze through my dreams with a din loud enough to awaken me and perhaps even the dead. This morning I wanted to watch the launching first hand and learn the history of these missiles-from-dream-hell, that so often interrupt my sleep.

It was 6:15 a.m. and the sun was just peeking its brilliant orb over the mountains to the east, tinting the sky salmon pink as I walked from my home towards Barrio Cerrillo church. I knew the barrage would continue every five minutes, until at precisely 6:30 a.m., a fusilade of bombs would shoot forth, announcing morning mass in honor of Señor Transfiguración, the barrio’s principal yearly celebration.

I entered the Cerrillo church’s hidden patio, cloaked in smoke, in time to witness the spectacular early morning launch. I watched the three coheteros, whose duty it is to rise with the sun and propel, by hand, cohete after cohete into the dawn’s misty sky. I noticed bundles of future frenzy wrapped in white paper resting on a low table shielded from the flying sparks.

Launching of cohetes, homemade skyrockets, is a tradition in Mexico going back centuries when the noise was considered to scare away the devil and vanish all evil. Today they are often used simply for amusement. They are used, and sometimes abused, for every festival, funeral and public gathering in San Cristobal. Barrios endeavor to outdo each other in the number of cohetes and bombas (enormous firecrackers) they explode at their annual festival.

Barrio Cerrillo, where I live, is famous for its lavish use of cohetes and bombas, especially during festivals. Every day for nine days, from July 27 until August 6, Señor Transformación is honored by dozens of cohetes, exploding from the church’s secluded courtyard. Ancient bronze bells toll also, but they are just not loud enough to bring all the faithful to mass, hence the cohetes and their certain ability to awaken. Cohetes will be skyrocketed throughout the day to signal the many masses.

A cohete is usually a white wrapped cylindrical package 6 cm in diameter by 25 cm in length. This package is divided into the propulsion unit which is made from carrizo (a type of tall bamboo-like grass) and gunpowder and connected to the bomb, which is quite substantial at about 200 grams. This package is connected to a marsh reed of 1 cm in diameter by 1.3 meters.

Firing a cohete is surprisingly easy; first a small notch is scribed in the bottom, then a lit cigarette or smoldering branch, ignites the loose gunpowder to propel it skyward. The men hold the long, narrow missile upside down until sparks begin to fly from the base. Then, righting it, they launch it with an upward motion of their arm propelling it into the dawn’s early glare. Dangerous, indeed, because at times the cohetes rise only a few meters then explode with the force of half a stick of dynamite. Traveling seemingly at the speed of light, fireworks ascend heavenward, leaving a brilliant cola of red twinkling stars dancing in the brilliant orange morning sky. At about 150 meters, they explode with a resounding and deafening concussion, awakening several more souls.

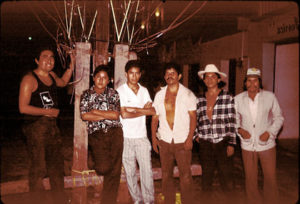

After the 6:30 am blastoff, the coheteros are pleased to share with me the history of their art. Obviously they take considerable pleasure in waking the sleeping people of Barrio Cerrillo and beyond. Javier, the eldest and official spokesman, has been with the church since his youth, when he would assist his father with the ballistic wake up calls.

Javier vividly remembers when he fired his first cohete, at age six, in the patio of his family’s home in the Barrio Cerrillo of San Cristobal de las Casas, Chiapas. He was at once excited and frightened that day, for the cohete is a symbol of manhood–dangerous, aggressive, violent…and taller then he. He feared that if he did not let go in time he would be carried aloft never to return to the Cerrillo. He was cautious and trembling when he lit the end with a burning ember, but as the cohete soared from his tiny hand and exploded perfectly in the mid-day sky, he smiled, and his father was overjoyed.

He recalls another moment, 40 years ago, when he first set out before dawn to actually work with his father, one of the official coheteros of Barrio Cerrillo. He was trembling as he told me the tale, and I could see in his eyes that he was reliving the experience once again. Javier had just turned thirteen and was as frightened that day as when he was six. He worried that he might have a dud. Or, what if the cohete wouldn’t light! Or, what if it took a downward turn and landed in the church! If any of these things happened, he would be forever banned from the cohetero society and an embarrassment to his father.

However this special morning, gracias a Dios, the cohete zoomed straight into the dawn’s luminescent mist and exploded, sending Javier and his proud father into screams and applause and delight. In the old days, as today, the cohetes were used to awaken the people to attend mass, but Javier explains that they would use one or two, never the hundreds that are used today.

I asked where the cohetes were made and Poncho, Javier’s helper, told me that all cohetes are made in Barrio Sta. Lucia, just a few kilometers from Barrio Cerrillo. Barrio Sta. Lucia has been the barrio of the coheteros for numerous years. Reeds for the stabilizers are collected in the tierra caliente, from ponds and along the many rivers. Tubes for the rocket engine are bought from carrizo vendors, who bring the tubes, which are 4 meters long by 4 to 6 centimeter wide, into the city from their gardens in the low valleys of Chenalo, 30 kilometers from San Cristobal. The white paper that wraps the bombs is purchased from used paper dealers. Raw material for the propulsion is potassium nitrate or potassium chlorate, charcoal, sulfur and other inert filler materials, purchased from the local ferretería (hardware store).

Assembling of the cohetes, which is a job done only by men, takes about twenty minutes each. Once assembled, they are wrapped in white paper in bundles of twelve and sold for 60 pesos. On Saturdays, when outsiders come to San Cristobal to shop, one often sees men carrying many bundles of cohetes on their shoulders as they return to their villages in the surrounding hills and valleys, anxious to celebrate the town’s festival or personal celebration by launching cohete after cohete.

The coheteros tell me that this year the Barrio Cerrillo festival will fire over 30 bundles of 12 each – 360 cohetes, — each one resounding and rattling my nerves and interrupting the sleep of all who live within earshot of the Cerrillo church.

I thank the coheteros, happy and pleased with the first-hand, behind-the-acrid-smoke, account of the morning’s POP POP POP! As I leave, the coheteros give me a ‘going-away’ present. Each sends aloft a skyrocket at the same time. They explode simultaneously as I pass under the arch leading to the plaza in front of the Cerrillo church.

Ah, another mass is to begin.

Photo Strips of Cohetes y Coheteros – #43 -|- #44

with regard to cohetes, they are absolutely terrifying to the animals within hearing distance. The levels of sound are also harmful to human hearing and since dogs and cats can hear about 10 times the Hz level we can, are physically painful and the equivalent of animal abuse. On All Saints Day, I rescued a dog frozen in terror under the wheels of a truck. He had been abandonned by his family which had sold their house and moved to another city. The cohetes in Ajijic started a few days later to celebrate San Andres. They are still going on, randomly, and at any hour between 4:40 am and 11:45 pm. This dog was only able to get out for exercise and elimination from midnight until 4:00 am for the past 3 months. I used to really like this place. I can now not wait to find a rural setting far enough away to prevent the PTSD he suffers and the impact on my life quality due to them. They are not cute, not fun, and not reasonable. They are dangerous in the short term, but more so in the long term. They have been abused, and abused, and abused and now, should be eliiminated or at least controlled to be used as originally intended and agreed. ONLY. Looking around at the number of families with real physical need, the funds poured into cohetes could have a much finer impact on the Mexicans than the explosives. I sternly warn those people travelling with pets, PTSD associated with war, or mental illnesses affected by sudden excessively loud sounds to avoid Ajijic from October until February. I understand it is worse this year than last and that the pattern described in the article is progressing here as well.