¿Te gustan los toros?” asked eleven-year-old Maggie. Her eyes scanned my face looking for a yes.

Did I like the bulls?

A bullfight? I flinched at the thought. Earlier during the week, I’d jumped at my young friend’s invitations to enjoy all events at La Fiesta de Virgen de Guadalupe. But now, visions of bloody bulls prompted my swift reply, “No! Gracias.”

Maggie’s mouth twisted, perplexed. Was she thinking that the gringa-worm had turned since yesterday? She tried convincing me in rapid Spanish. Unmoved, I resolved in my mind: stand your ground, Devlin. You’d like to please this girl …but just say no! Looking her straight in the eyes, I mouthed slowly, “Read my lips. NO. WAY. JOSE!”

Maggie only flashed a grin. Flouncing her long brown hair, she turned in her sneakers and scampered from the dining area of the casita. Relieved, I nibbled at my plate of delicious botanas.

My husband Bill and myself were guests of our friend Roca Sayula and his wife Gabriela. Roca contacted me by e-mail after he discovered my series of stories about his home village of Melaque. Over the past year we grew to be E-friends, which resulted in an invitation to visit his home in the small colonial city of Cuidad Guzman, Jalisco. From our apartment near the beach-town of Barra de Navidad, Bill and I took three different buses to travel inland 100 miles. Cuidad Guzman, population 100,000, is located about mid-way between Guadalajara and Manzanillo in a prosperous agricultural valley.

At the University of Guadalajara campus, Roca is a professor of veterinary science. He and his veterinarian wife, Gabriela, also run a small farm and pig insemination business. After we stayed several days in their home, they invited us to La Fiesta de Virgen de Guadalupe in Gabriela’s hometown, an hour’s drive into the countryside.

Every year, from near and far, Gabriela’s extended family reunites in the five homes that they still own near the small town plaza. Bill and I squeezed into the backseat with Roca Jr. age six, Glorita, four, and Carlitos, two.

Their holiday casita fronted the plaza, sandwiched between the town hall and the main grocery store. When the casita’s great wooden doors opened, I faced the beloved church, Santa Maria Magdalena, bright in daffodil yellow. In traditional Mexican fashion, the secular and the sacred face each other across the communal plaza. I could walk straight out the door, through a beer garden, past the central kiosko, or bandstand, across an expanse of concrete and upstairs into the church. Best of all, the casita offered a front row view for the lively two-week fiesta.

Their holiday casita fronted the plaza, sandwiched between the town hall and the main grocery store. When the casita’s great wooden doors opened, I faced the beloved church, Santa Maria Magdalena, bright in daffodil yellow. In traditional Mexican fashion, the secular and the sacred face each other across the communal plaza. I could walk straight out the door, through a beer garden, past the central kiosko, or bandstand, across an expanse of concrete and upstairs into the church. Best of all, the casita offered a front row view for the lively two-week fiesta.

Not taking NO for an answer, Maggie rounded up some of her twenty cousins who were also visiting during this holiday. They formed a ring around my chair. Six pairs of brown eyes intensely scanned my entire being, from my middle-aged head to worn-out sandals.

I looked at the mothers in the casita kitchen. Gabriela and her three sisters were chatting while they cut and cooked fresh meat for snacks. Their husbands had all mysteriously disappeared, but the ladies didn’t seem to be leaving for the bullfight. I wondered to myself if the kids needed me to take them.

I called to Bill, “The kids want to go to the bullfight. I really don’t want to go. But I think they need an adult.”

With a casual swipe at my botanas, Bill replied, “Why not? Let’s check it out. We can always leave early.”

I could tell that Bill was up for a Mexican adventure. I glanced at the kids. They locked me in their gaze. Slowly, I turned to Gabriela to ask for permission. Secretly, I hoped for a refusal. I waited until she finished slicing a hunk of beef. She answered with a beaming smile and a wave from the cutting board.

Half-heartedly, I stood up and called the kids. “O.K. You win. Vamanos.”

Maggie’s smile lit the casita. She bounced towards me, reaching out her hand, “¡Tome tu suéter!”

“A sweater? Whatever for?” I wondered out loud.

It was four o’clock on a sunny January afternoon and eighty degrees. Perhaps the temperature dropped in the evening. After all, this plateau nestled high under the smoking Colima volcano.

“Maggie should know the score,” Bill said. “I bet she’s been going to bullfights since she was a baby.”

By the time we left the casita, six more children joined our parade.

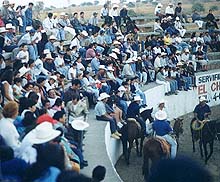

After climbing the stairs to the bullring, Bill bought eight tickets for nine pesos each. Among the crowd, I spotted Ina, the sister-in-law of our friend Roca. She waved us over to join her children and relatives. People crammed onto the lower seats and exuberantly up the tiers. I squeezed onto the seat beside Ina. From a top tier to the south, a brass band launched a rousing tune. A cheer went up as the three bullfighters or toreros entered the ring.

After climbing the stairs to the bullring, Bill bought eight tickets for nine pesos each. Among the crowd, I spotted Ina, the sister-in-law of our friend Roca. She waved us over to join her children and relatives. People crammed onto the lower seats and exuberantly up the tiers. I squeezed onto the seat beside Ina. From a top tier to the south, a brass band launched a rousing tune. A cheer went up as the three bullfighters or toreros entered the ring.

The smallest torero, slender and slight of build, faced the audience and bowed. Thick foundation make-up covered a small oval face. Greasy hair crème generously slicked back his dark hair. Long sideburns, etched with a black felt pen, stretched towards his smooth chin. I estimated his age somewhere in the thirties.

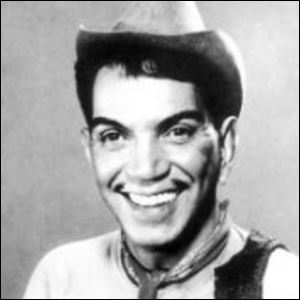

His immaculate front shirt gleamed white under his black ribbon tie and golden brocade jacket. But over-sized dirty brown pantaloons sagged off his hips. Barely controlled by a thin green sash, one false move might reveal everything. But again, that might be the idea. When he turned, I noticed his jacket hung together in three ragged pieces. With a big grin, the bullfighting clown began dancing upon the spot. Poufs of dust rose under his feet. He heckled the audience. Ina turned to me, chuckling, “He’s like Cantinflas,” she explained. “The charlie Chaplin of Mexico.”

I’d never heard of Cantinflas, the professional name of Mario Moreno Reyes (1911-1993). He became the most popular entertainer in Latin America and starred in many Mexican motion pictures from 1936-1981. His films included “Ni Sangre, Ni Arena” (Neither Blood, nor Sand; 1941), a satire on bullfighting and the Hollywood film classic “Around the World in 80 Days” (1956). He came to worldwide attention in the role of “Passepartout” when this film starring David Niven, Buster Keaton and Shirley McLaine won five Academy awards. After his next Hollywood film, “Pepe” (1960), he returned to Mexico and continued to star in highly popular comic films.

I’d never heard of Cantinflas, the professional name of Mario Moreno Reyes (1911-1993). He became the most popular entertainer in Latin America and starred in many Mexican motion pictures from 1936-1981. His films included “Ni Sangre, Ni Arena” (Neither Blood, nor Sand; 1941), a satire on bullfighting and the Hollywood film classic “Around the World in 80 Days” (1956). He came to worldwide attention in the role of “Passepartout” when this film starring David Niven, Buster Keaton and Shirley McLaine won five Academy awards. After his next Hollywood film, “Pepe” (1960), he returned to Mexico and continued to star in highly popular comic films.

Cantinflas had a flair for parody. The actor perfected comic speech known, as ‘indirectas’ in lines like: “There is somebody here whose name I won’t say but I am looking at him.” Even a new verb, cantinflear, was invented to describe his style of speaking. Cantinflas could speak volumes while saying nothing of importance. His absurd adventures combined inborn wisdom and naïve good luck. His popularity grew with his roles. He refused to feel inferior to civil bureaucrats, highly decorated police chiefs or even famous haughty bullfighters. Thus, in the class-ridden Mexican society of the 30’s, 40’s and 50’s, Cantinflas’ popularity rests in his portrayal of equality between people. To those persons pulling birth rank, social status or pompous pretensions over others, Cantinflas gave a clear message: “Hey! Come on, we’re all just men.”

As we watched, this latter-day Cantinflas pretended to conduct the band from the bullring. Then he clowned with his bull cape. The other two toreros played his straight men. The silver haired lead bullfighter stood impassively in the center of the ring. Dirt dusted his tight fitting red velvet pants. Slowly, he brandished his red cape at an imaginary bull. The second man scrutinized the door of the bullpen. A jacket of black satin with gold braid tugged at his chest. As the man swished his cape, he looked the romantic hero of fiction and poetry.

As we watched, this latter-day Cantinflas pretended to conduct the band from the bullring. Then he clowned with his bull cape. The other two toreros played his straight men. The silver haired lead bullfighter stood impassively in the center of the ring. Dirt dusted his tight fitting red velvet pants. Slowly, he brandished his red cape at an imaginary bull. The second man scrutinized the door of the bullpen. A jacket of black satin with gold braid tugged at his chest. As the man swished his cape, he looked the romantic hero of fiction and poetry.

I mused: Is Los Toros a scaled down version of a Spanish bullfight? Where are the weapons for torturing and killing?

All of a sudden, the gate on the lower east wall swung open. Six horsemen cantered into the ring. Several men rode to the ring’s tall sides to chat with the spectators. Others pranced their well-groomed horses to the music on the spot. With a blast of trumpets, the first bull burst through the gate. On his bucking back, jolted a young cowboy or ranchero. He clung with his knees; his hands grasping only a thin rope heaving on the bull’s belly. Five seconds, a few mighty leaps and the bull rider flew through the air. As he thudded onto the dirt, the crowd gasped. The ranchero scrambled to escape the bull. The crowd clapped wildly. The bull paused, snorting in the center of the ring. Cautiously the three bullfighters approached.

Lowering his head, the bull began scraping the earth with a front hoof. He eyed the toreros and shook his head. With a flourish of capes, the men provoked him to charge. The bull charged Cantinflas. The clown dodged his attack. With a sweep of his cape the lead torero distracted the bull’s attention. The bull turned and charged towards the new target. When the animal missed again, the third torero lured him across the ring. The bull charged off in the new direction. Within a few minutes, the bull tired of the teasing chase. He stood motionless, flecks of foam clinging to his mouth.

Spurred by his inactivity, the mounted rancheros stampeded the bull. He raced around the ring. The horsemen chased, twirling ropes, until one deft lasso slipped over the bull’s hind feet. He crumpled. Leaping from his horse, a ranchero swiftly untied the rope from the bull’s belly. With a struggle of hooves, the bull scrambled to his feet. Murderous horns plunged at the heels of the fleeing ranchero. The crowd applauded. The other rancheros drove the bull towards the open door.

Spurred by his inactivity, the mounted rancheros stampeded the bull. He raced around the ring. The horsemen chased, twirling ropes, until one deft lasso slipped over the bull’s hind feet. He crumpled. Leaping from his horse, a ranchero swiftly untied the rope from the bull’s belly. With a struggle of hooves, the bull scrambled to his feet. Murderous horns plunged at the heels of the fleeing ranchero. The crowd applauded. The other rancheros drove the bull towards the open door.

In two hours, six bulls entered the ring. One by one they threw the young rancheros in the dirt. Between bulls, Cantinflas mimed and joked with the crowd. Vendors hawked cervezas and refrescos from ice-filled plastic buckets. Small boys peddled peanuts, candy and chewing gum. A tower of packaged snacks approached Ina. She bought a bundle for the kids. Once they were all busy eating, she eyed me thoughtfully. With a sweep of her hand towards the bull ring, she asked, “You like Los Toros?”

“I do, especially now that I see the bulls are irritated, but not hurt.”

Ina tugged her shawl over her small daughter nestled in her lap. A smile curved her lips. She explained softly in careful English, “This is the second show. The best bulls ran first. These ones are just babies.”

Like the toreros and the rancheros, Ina also belongs to Los Toros. Her gentle manner makes it hard to imagine her herding bulls. But Ina grew up on a small ranch or ranchito several miles out of town. When she was four, her parents built a house in town. Like the surrounding families, they continued going to work at the ranch everyday.

These days Ina’s home is a thousand miles away in Los Angeles. But every winter, she tries to return with her husband and four young children to their hometown in southwest Jalisco. The small colonial town of five thousand serves, as a social and spiritual hub to the area’s many scattered ranchitos. It’s narrow cobblestone streets reveal two to three horses or donkeys tied up per block. There is no hotel or bank. Nevertheless, 30,000 devotees or hijos de La Virgen de Guadalupe find room to stay during the two-week fiesta.

Twin traditions of raising corn and cattle twine into the fiesta. Horsemanship and rope skills from work-a-day ranch life mix freely with food, music and entertainment. This espectáculo or show with its parody of a bullfight is called ‘charlotada’. Cantinflas and his bullfighting friends are hired to inject humor and excitement into the fiesta mix.

Although I hadn’t sipped a drop of alcohol, I felt intoxicated by the goodwill and laughter. At the late afternoon charlotada, hearts beat to a common pulse. Also I felt warmed by the way Roca, Gabriela, Ina, Maggie and the rest of their family had embraced us into their life. I find the Mexican-style social intimacy refreshing and stimulating.

As the last rays faded behind the purple mountain peaks of the Sierra Madre, a chill wind suddenly whipped the bullring. Shivering, I reached into my bag for the sweater. Minutes later as I pulled the sweater even closer, I welcomed the closing announcements. Our little guides resurfaced from the crowd. Unfolding my knees, I rose and climbed down the tiers of the bullring.

Four o-clock the next afternoon Maggie showed up at the casita with her twelve-year old cousin Luce. “¿Vamos á Los Toros de nuevo?”

This time I thought: A second charlotada? Why not?

Stretching my hands to the girls, I called to Bill, “It’s time to go to Los Toros!”

The girls and I skipped downhill on the narrow sidewalk, which hugged the cobblestone street. Along the way, six more cousins joined us. We joked and chatted while walking towards the bullring. Inside, Bill turned right and climbed to the top row to take better photos of the events. The rest of us turned left towards some empty seats further along the walkway.

Unexpectedly, the bullfighting clown blocked our path. Cantinflas stuck out a white-gloved hand, blowing shrilly on his whistle. He blew again and waved us on. We started to walk. The white glove flew up in the air and the whistle blasted again. We stopped. Another loud toot and he waved us on…then back. On again, then back.

With the kids and I bouncing between whistle blows, the crowd roared with laughter. I glimpsed new mischief flickering in the clown’s eyes. Oh, no, he’s up to something, I thought. And I’m the only gringa in town!

At the next whistle blast, I cupped my hands to my head. Snorting like a bull, I charged past Cantinflas. The kids hustled behind. Caught off-guard, the clown blew his whistle hysterically at our backsides.

Seconds later, Cantinflas tracked us down across the ring. He rattled Spanish at me. All I understood was that he wanted me to do something. With the crowd watching, I felt shy and a little embarrassed. Snuggling to Maggie and Luce, I shook my head no.

The clown’s painted eyebrows arched over his dancing eyes. With a jerk of his head, Cantinflas saluted me. Twirling in a semi-circle, he strode to the other side of the ring. Unhooking a microphone on the stage, he requested a boy and a girl to come up. From the crowd, a twelve-year-old boy stepped to his side. Cantinflas appealed again for a girl. We urged the out-going Luce forward. She dropped her purse and candies and raced to the bandstand. Cantinflas explained the rules for the contest.

He instructed the two kids: First the boy must yell, “Camaron.” (shrimp). The girl must answer, “Caramelo.” (caramel candy)

The shouting match started. The war of words leapt back and forth. Volume climbed steadily until the boy flubbed his word by shouting ‘caramon’, a nonsense word. Round one went to Luce. Cantinflas invited another boy up to the stage and the game began afresh. Meanwhile, Cantinflas kept up his banter, trying to flummox the contestants. The match grew nosier. Suddenly, Luce blurted “carmelo.” She dissolved into laughter. The contest was over.

Some of the spectators perched on the concrete walkway eight feet above the bullring. Most of the cousins joined them. In my Canadian head, a voice whispered safety warnings. As the bulls charged and rancheros galloped below, I hovered behind the youngest boy of four. My hands reached out ready to grab his shirt. Our friend Roca and his two-year-old son Carlitos showed up. Nine rancheros cantered into the ring. One of the horsemen is his brother-in-law, Marcos. The ranchero rode straight over to Roca who handed him young Carlitos. Plunking the baby in front of his saddle, Uncle Marcos toured him proudly around the ring. Baby returned to papa just ahead of the charge of the next bull.

I marveled, “Never see anything like this in Canada! They’re not wearing helmets either!”

Before the next bull event, Cantinflas frolicked in the crowd. He carried an over-turned sombrero as a collection plate for the performers. The clown spotted Bill sitting at the top of the tiers. He climbed to reach the gray-haired gringo. Bill grew up experiencing small country fairs in England and Ireland. He loved the atmosphere and decided to have some fun with the clown. Bill placed a large peso coin on the back of his left hand, hiding its face with his right palm.

Cantinflas joined the game immediately. First the mime shook his head thoughtfully. Then he pressed his fingers to his scalp and rolled his eyes. Playing a clairvoyant, he continued to guess wrong. At his parody, the crowd howled with laughter. As Bill became the butt of the performance, he joined the laughter and finally flipped the coin into the hat. With a smile like a floating slice of moon, Cantinflas tipped an imaginary sombrero goodbye. He carried on, soliciting the audience.

At each new thunder of hooves out of the chute, the crowd tensed in anticipation. Breaths sucked inward as each bull threw his ranchero. Six more bulls dealt danger to the toreros. When one bull charged Cantinflas, somehow the animal flew up the tall wall of the bullring. The spectators scattered. Cantinflas fled behind a protective fence. All escaped the legendary glorious death on the horns of a toro. Around six p.m., the excitement ended. People stood to leave for the pilgrimage and mass for the Virgen de Guadalupe.

I enjoyed my first charlotada in that small town in Jalisco. Going to a bullfight turned out differently than I expected. The espectáculo or show had a few thrills and chills but no intentional gore. The social atmosphere intoxicated me. I enjoyed the antics of Cantinflas, the rodeo clown. Perhaps I identified with his wild brave heart, which, I believe beats inside us all. The original Cantinflas, Mexican actor Mario Moreno, reminds me of the Spanish words: “La primera obligación de hombre? Ser feliz y hacer feliza los demás.” (The primary responsibility of man? To be happy and make others happy.)

Los Toros had finished for the day. Little did I suspect that Cantinflas held more tricks for us up his sleeve. I fell under the spell of Mexico and the evening was still young.

RESOURCES:

- CANTINFLAS, professional name of MARIO MORENO (1911-1993)

- Mario Moreno Cantinflas El Pelao Azteca (Spanish)

https://www.ciudadfutura.com/comicoscine/cantinflas.html - As you read the biography and list of fifty-one films made from 1936-1981, old-fashioned fairground music plays in the background.

- Biography of Cantinflas featured among famous stars of comedy. Click on his retreato-photo to link to four photos from his career.

- Un Siglo, Diez historias Cantinflas (A Century, Ten Stories) Spanish

https://www.bbc.co.uk/spanish/seriemilenio06.htm - British Broadcasting Company serving Latin America from London. Photos and interviews (Real-Audio) with actresses and family members who remember Cantinflas Mario Moreno (1911-1993). Site also features the free interactive Spanish learning program ‘Sueños’-world Spanish.

- Hoy Siglo XX Today’s Twentieth Century-February 1999 El Personaje (Spanish)

https://www2.hoy.com.ec/sigloxx/04febre.htm

Mexican Espectaculos – Series Index

This is part 3 of 5

- Introduction to the Series

- Part 1: Charreada in Guadalajara

- Part 2: Receiving End of a Mexican Rodeo (Recibímiento á Las Fiestas Taurinas)

- Part 3: The Bullfight and Cantinflas

- Part 4: Cantinflas, the Castillo and Ponche in the Plaza

- Part 5: Gold Trail to Santa María del Oro, Nayarit

Published or Updated on: January 1, 2001