Certainly Sr., fortunately here in Michoacán, we still have handcrafts, our heart and these hands. And with these we can do a little bit of everything…”

– Source: “El quehacer de un pueblo” (“The tasks of a town”), Casa de las Artesanías de Michoacán (The Michoacan House of Handcrafts).

This article is a guide to the highways and byways of Michoacan´s handcraft routes, through the highways and byways of the Soul of Mexico.

Michoacan is not only history, culture, tradition, customs, fairs, celebrations, dance, music, gastronomy, architecture, archeology, natural beauties and a diversity of landscapes. Michoacan is also world-renowned for its production of handcrafts. Currently there are more than 30 different varieties of handcrafts that are classified in such varied groups as pottery, metal work, woodwork, textiles and vegetal fibers. Most of these handcrafts originated prior to Spanish colonization of the state and, today, many of them are still being produced using the same ancient techniques.

An excellent display of Michoacan’s handcrafts can be admired at the Palm Sunday Handcraft Market in Uruapan.

To help you find your way around Michoacan, the article is divided into six regions: Morelia, Pátzcuaro, Uruapan, Zamora and Lázaro Cárdenas. Each one focuses, firstly on the major city and is then followed by complementary information about the craft that is produced in the different towns.

Getting to know and admire Michoacan’s handcrafts means getting to know the Soul of Mexico.

Welcome!

HISTORY

Several studies have shown that around the year 900 A.D , metal was already being worked on the American tableland. In the region corresponding to what today is Mexico, the Mayan area, Oaxaca and Michoacan have been signaled out as major metal working centers since before Spanish colonization, indicated by both the diversity and the age of objects that have been found there. However, Michoacan stands out for having elements with their own distinctive features, the oldest remains having been located around the Patzcuaro Lake.

In ancient times, a privilege of the prevailing religious or political group was to own metal objects – mainly ornaments and jewelry. These were also objects offered to the gods or to the dead. In some cases, the objects produced were also used in daily work, which were made in sets using molds. Among the pieces manufactured, those that stand out are: needles, wires, pins, rings, fishhooks, bands, hoes, ornamental poles, special rings that were designed to be worn in the lower lip, bracelets, small bells, ear guards, pliers, punches, pipes and bowls. These objects could be made either in gold or in copper.

Among the techniques mastered by ancient Michoacan people are martillado, or hammered metal, metal coating, metal casting with open and closed molds, one example being the so-called “lost wax”. For metal work, as well as the techniques for other crafts, full time specialists were required. In the Tarascan society prior to colonization, people were grouped according to their major field of expertise.

Besides metals, feathers were also considered valuable objects in the American tablelands. Artifacts created from feathers were designed for the gods, priests and political leaders, since feathers were a sign of power and dignity. Feather art was also an activity carried out by specialists, who were called “izquarecucha” in the native language of the people of Michoacan. With feathers from different birds they made capes, blankets, clothing, buckles, ornamental staffs using tufts of feathers and flags hanging from long canes. Such craftsmen cut feathers into small pieces and then combined different colors to mark out their designs, which were made with various techniques according to the object to be created.

Among the different groups of craftsmen that existed prior to colonization, those who specialized in metallurgy and feather art were considered the true artists and the most important within the larger group of artisans. Nevertheless, other techniques are also recognized for the high quality of the products created, such as woven textiles, ceramics and stone carvings. Apparently, the value of these was due more to the role they played as economic or religious status symbols.

The Michoacan Relationship refers to the spinning and textile activities that were carried out exclusively by women, skills that were passed on from generation to generation by mothers to their daughters. Among woven garments that were made the most significant were shirts, cloths, female clothing, threads used to create head-dresses and doublets for war. Cloths were made of varying thickness and colors or were decorated with feathers or rabbit fur; it is important to mention among all the cloths manufactured, white cloths were used as currency or as gifts for the gods. Woven fabrics had several purposes, not only used for bedding, they were also used to wrap the dead, for bartering or as gifts.

Manufactured materials were created from vegetable fibers taken from the maguey and agave cactus, white or dark cotton, indigo and different woods. Fruits or insects were also used to produce dyes to obtain such colors as blue, black, reds and white.

Clay was one of the most important materials used by inhabitants of the area prior to colonization.

Archaeological discoveries of ceramic artifacts have enabled us to learn about the technological developments of the people who produced them, as well as helping to identify different cultures, trade routes and areas of distribution areas or contribute to the elaboration of more precise chronologies. The ceramic produced by the Purepecha people was characterized by being polychromatic with decorative painting elaborated in negative. The predominant color was black and combined mainly red and white; this was one of the most outstanding techniques from the pre-colonial era of Mexico.

In Michoacán the best examples were located around the Pátzcuaro Lake. Ceramic designs created in the negative have been considered the most representative of the Purepecha culture; it appears that the ceramic was manufactured by specialist craftsmen, given the complexity and richness of form and decoration that is found on the pieces.

Among the manufactured objects that stand out are earthenware bowls, pots, gourds, vessels made from fine clay, among them miniature pots with the typically Michoacán colors and designs, as well as pipes, figurines, whistles, and pots.

Other areas of Michoacán where ceramic production became significant earlier or contemporaneously with the development of the craft in and around Lake Pátzcuaro include the areas around Zamora, Cojumatlán, Zinapécuaro, Apatzingán, Tecalpatepec, the coast and the shores of the River Balsas, Huetamo, Morelia, and Cuitzeo.

Turquoise and other semi-precious stones were usually combined with the creation of obsidian objects. These craftsmen, along with those who worked with feathers and metal, had a recognized status, and when they died their materials and work tools were buried with them.

Obsidian crafts were used as farming, hunting, and military tools, as well as for religious purposes as sacrificial knives and sumptuary objects. The main obsidian mines were those of Zinapécuaro (“obsidian place”). The Tarascan State probably controlled mining, because these mines held economic value as a source of raw material. Other objects such as polished green stone, in tubular and spherical shapes, had a symbolic value with religious meaning. Finally, in relation to the same stone work, illustration XXVIII of the Relation of Michoacán depicts stonecutters, extracting stones of the quarries and cutting it for the covering of religious buildings such as the Yácatas.

Today each these artisanal activities continues, some using pre-Hispanic techniques, some using mestizo techniques (a blend of pre-Hispanic methods complemented by those introduced by Europeans during the Colonial era), and others using modern-day methods such as high-temperature firing and violin-making.

The Casa de Artesanias (House of Handicrafts) in Michoacán separates artisanal activity among several branches: Pottery, classified as burnished or polished clay, multi-color, high temperature fired, glazed, and smooth-finished; Metalwork, exemplified by jewelry, blacksmithing, and hammered copper; Wood, classified by sculptures, carving, manufacture of stringed musical instruments, furniture, masks, lacquerware, maque and leather chairs; Textiles, distributed between embroidering, open and drawn work, fabric woven on backstrap and foot-pedaled looms, and hook-woven materials; and Vegetal fibers, composed in reed, tule, bulrushes (chuspata), palm and wheatstraw. One final branch includes toys, leatherwork, stonecutting, wax, pattern-cut paper (papel picado), corn leaves, featherwork, straw painting (popoteria), and pasta de caña (sculpture made from a mixture using the inner core of cornstalks).

CRAFT FORMS

POTTERY (ALFARERIA)

The potter creates works which are not only simply characteristic of a region but of a specific town, bringing to his work the collective experiences of the potters before him while still imprinting his unique mark on each piece. The common accents identify a potter’s product with its provenance, heralding the community from which it came. Many potters also work in other occupations such as farming, but the pottery of these communities is what has earned these towns international recognition. The potters’ workshops are the important part of each community’s fiestas and the reason for the region’s fame. The potter’s entire family usually participates in the beginning stages of the craft, starting with harvesting the raw material, sifting it, dampening and kneading the mud into clay.

BURNISHED CLAY (BARRO BRUÑIDO)

Burnished clay is a kind of pottery that has been polished into bright, fine sheen. Creating this effect requires the use of different tools such as a wood or stone polisher or even a corncob. The product is massaged, rubbed and caressed until it shines. Without doubt, the main burnished piece is the pitcher which holds refreshing drinking water. It is developed in Tzintzuntzan, Patamban, Zinapécuaro, Cocucho, Huáncito and Ichán.

MULTI-COLOR POTTERY (BARRO POLICROMADO)

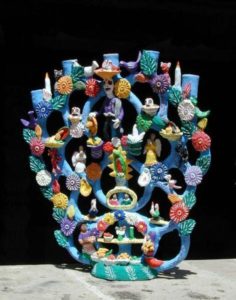

Polychrome pottery is multi-colored. After the raw materials have been ground, sifted, dampened, kneaded and formed into clay figures, another step in the process is added: decorative paint from cooked anil. The women of Ocumicho produce their multi-color sculptures of impressive scenes taken from the Bible as well as daily life, adding a unique twist: the Devil at play. Sometimes the Devil might appear in scene of the Last Supper, or simply coming between two lovers.

GLAZED POTTERY (BARRO VIDRIADO)

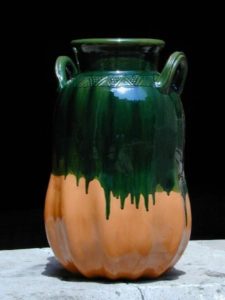

The glazed finish resembles enamel or glass. Once the piece is shaped, it undergoes a two-step process. The first firing bakes and hardens the product, and the second cooks and seals the glaze, creating a greater variety of styles and colors than simply those which came from the clay. Towns like Patamban and its green stoneware and delicate fine dishes, Capula and its pointelle and sometimes ornate designs of its pots, casseroles, and dishes, Tzintzuntzan and its pots and serving pieces, Santa Fe de la Laguna and its traditional black incense burners and candelabra decorated with tiny drops, San Jose de Gracia and its famous pineapples, Zinapécuaro and its dip-glazed pieces, and Santo Tomás and Huáncito — all are dedicated to glazed pottery.

SMOOTH-FINISHED POTTERY (BARRO ALISADO)

The most basic but no less beautiful form, with its simple and round shaped pots and griddles is produced in Zipiajo and various Nahuatl communities along the coast.

HIGH-FIRED POTTERY (BARRO DE ALTA TEMPERATURA)

Clay fired at high temperatures in a gas kiln and then glazed requires sophisticated techniques, but the technique produces the dishware, flower vases and fountains with beautiful touches which can be found in Patamban, Tzintzuntzan and Morelia.

METALWORK (METALISTERIA)

Jewelry in Michoacán is represented by fine works created by groups of Mazahua origin, based in Zitácuaro, as well as in Huetamo. The earliest jewelers used silver, and then they later moved on to low-carat gold, combining their work with filigreed traditional pendant earrings. Mazahuas set the standard for refinement and artistic quality which later became part of the final ornamentation in the greater temple of Tenochtitlan; after the Spaniards arrived, the Mazahuas were assigned to work in the first mint established in Mexico in 1536.

In Cherán silver flat and pendant earrings were made in the shape of the half moon, an indigenous symbol. Uruapan is known for works of gold of varying carats, flat and engraved pendant earrings, necklaces called “caricias,” and chain. Pátzcuaro is known for necklaces made of orbs of carved silver combined with hollow drops, beautiful designs with coral and medallions, fine silver wires and tiny elaborate decorative fish.

Michoacán is renowned in México for the hammered copper of Santa Clara del Cobre, a town founded in 1530 after the construction of an enormous smelter for the nuns of the Order of Santa Clara, who obtained official recognition of the town by 1553. Around the end of the 17th Century, a huge foundry fire burned down most of the town and the convent.

Reconstruction began in the early years of the 19th Century, and workers and company men flocked to the town, continuing the copper industry and establishing other businesses, rebuilding Santa Clara de Cobre and reclaiming its stature as the quality producer of hammered copper tubs, vats, ladles, trays, sinks, basins, kegs and all forms of containers. Today vases, ladles, skillets, pots, fruit, plates, trays, jars, jewelry, miniatures are fashioned with rustic tools mallets, hammers, two-headed hammers, anvils, and chisels.

WOOD (MADERAS)

Michoacán is one of those areas where entire communities’ survival depends upon wood. The inhabitants of tropical as well as temperate forests are indigenous people and mestizos who combine food production with complementary activities in craftwork. Throughout history, these people took their water from the forests’ lakes and streams, and forests’ fauna gave them meat. Today, even more still rely upon the wood as a source of energy for household activities, artisanal workshops and small industry.

WOODCARVING AND WOODWORKING (Tallado y Labrado)

Woodcarving and woodworking is characterized as extremely delicate work in the creation of popular religious art. The creative activities of popular expression of the woodworking artisans unified and gave identity to the Purepechas. Each product reflects the differences and unique qualities of its community of origin.

MASKS (Máscaras)

A popular art intimately linked to community life, masks are created by those who are active members of a society or group. Masks are born of the traditions and present a sample of the cosmic vision of indigenous people. Each masks reflects the richness of popular art, the constant and continuing creative process, and its design is a vision and expression of the culture, making it alive and latent. In the Purépecha region, and Michoacán generally, the masks come to life in the traditional dances of the Moors and the Christians, the Devils, the Little Blacks, the Old People, the Ranchers, the Hermits, the Maringuias (men dressed as women) and Cúrpites (a Purépecha term for “those who get together”).

SPOONS AND BOWLS (CUCHARAS Y BATEAS)

The producers of spoons and flat shallow bowls are examples of a traditional production process that is maintained in a social organization similar to the ancient Purépechas. There are also purely ornamental bowls and trays decorated attractively with lacquer and varnish. Others are highlighted in gold, native plants, insects and earth. In the processing of trays, species such as harapiti, fir, aile, white oak (cucharillo) and cirimo are used.

MUSICAL INSTRUMENTS (Instrumentos musicales)

The production of stringed instruments – guitars, violins, violas, cellos, contrabasses, and large guitars – have great importance in the communities of Paracho, Ahuiran, Aranza, Cheranástico and Nurío. Artisans complete the entire process from selecting the proper wood to polishing the finished product. The manufacture of musical instruments has traveled along many roads, and today these instruments are made in a mosaic of Mexican woods ranging from fir, palo escrito, rosewood, pine, cirimo, mahogany, white cedar, tepamo, tecote, walnut, granadillo y galeana.

Production of furniture and articles for household use ranges from rustic to magnificent and distinct finishes. The carpenters of the mountain communities such as Capacuaro and Comachuén make chairs, dining room suites, and beds; the craftsmen of Arantepacua and Turícuaro make chests of drawers and benches. Higher-quality furniture is created in Pátzcuaro in colonial and antique styles and finishes. In Erongarícuaro are made trunks and dining room pieces. In Tócuaro, furniture of Mexican walnut (“parota”) is well-known; in Cuanajo white pine is transformed into cupboards, chairs, trunks, spoon holders, and headboards which are the most prestigious of Michoacán carpentry.

Leather Chairs and Benches (Equipales y bancos)

Uniquely Mexican, the leather-backed chairs and benches rest on a frame made of strips of bark harvested from the trees of the Tierra Caliente, the hotlands of Michoacán, and combined with small hardwood twigs and branches. The outer portions of these pieces are made from different, much stronger woods, and seat and chairback are joined to the base with a form of bindweed; the interior portion is composed of yet another kind of wood, usually coral or San Miguel, to secure the base.

Lacquer (Maque y Laca)

Lacquer blossomed during the Colonial era in Uruapan, Pátzcuaro and Quiroga, places where different methods were applied. In time, distinct differences became apparent. In Uruapan, the tradition of lacquer continued unchanged, but in Pátzcuaro a new style of outlining images in gold on the lacquer developed, and Quiroga concentrated upon brush-painted trays.

The manufacture of gold-painted laquers begins with cleaning the surface with a form of white gasoline and manganese and repairing any imperfections in the wood. A paste is applied (for dark colors, a primer), and then repeated layers of lacquer are applied until the surface is smooth and shiny. The surface is again polished, and more lacquer is applied, outlining the figures that will decorate the piece. After resting for 24 hours, finally tiny pieces of gold leaf are carefully and painstakingly transferred to the design with cotton swabs which have been impregnated with oil, highlighting only certain portions of the design. Colors are applied to the body of the design, shading the dark areas and bringing light to the pale portions. These contrasts bring life to the decorated object.

Applying lacquer to bronze uses a different method. When applied to the purest metal, varnish dissolves into a viscous liquid. It is applied directly with a feather to create delicate contours, while broad strokes are applied by brush. Later, the colors are applied using the same methods as mentioned for works of gold. Maque is a yet another application of lacquer upon a base of wood, generally a shallow bowl (batea), with the addition of an essential element – “aje,” an animal fat extracted from the female insect coccus axin from the Tierra Caliente. Other materials may include chia or chicalote oil, recently replaced by linseed oil. The lacquer paste includes a mix of dolomite limestone or lime-enriched plaster. In the Purépecha language, the mixture is called tepútzchuta. Colorants are taken from mineral-rich soil but some are derived from animal and vegetable sources.

TEXTILES

The raw materials used to make textiles are divided into two groups: smooth fibers such as silk, cotton and wool, introduced to the American continent by the Conquistadors, and hard fibers native to Mexico such as ixtle, lechuguilla, tule, palm, twigs, reed, and willow. In indigenous regions of Mexico, women are responsible for clothing the community, a process which often begins with harvesting the natural fibers and then spinning, dying, and weaving textiles. In Michoacán, backstrap looms of pre-Columbian origin and pedal-driven looms of European origin are both used to weave cotton and wool.

COTTON (Algodon)

The knowledge of producing textiles from cotton is transmitted from generation to generation, in a lyrical way that represents the lifestyle of a great number of families. This fabric is made into dresses, jackets, blouses, tablecloths, table runners, napkins, and open and embroidered work, bedspreads of vibrant colors, the most representative of which are made in Pátzcuaro and Uruapan. For men, there are belts, jackets and trousers of cross-stitched and embroidered cottons in several colors, exemplary of Zacán and Tócuaro.

Traditional rebozos, or shawls, of white and blue over a black background, woven in Ahuiran and Angahuan, rebozos de bolita (“tiny balls”) woven in La Piedad and Zamora, and the “guanengos” of Tarecuato, Cocucho and San Felipe de los Jerreros, embroidered in tiny cross-stitch, are the daily attire of the women, worn with a blouse whose shoulders and cuffs are bordered with intricate geometric, almost Grecian, patterns of embroidery.

“Guanengo” is a derivation of the huipil (straight, loose sack-dress) dating from the pre-Hispanic times seen in some indigenous regions of Mexico.

The openwork and embroidered blouses and guanengos can be made with different techniques such as straight stitching, cross-point, and tucks. In San Felipe de los Herreros are the finest examples of openwork dresses and blouses, also found in Zacán, Tócuaro and Erongarícuaro.

Náhuatl textile arts remain authentic, because the products continue to be made for self-consumption, although recently there has been some commercialization of original creations. The people of the coast continue planting cotton, spinning it, dyeing it with indigo, anil, purple and wood-based tints. The towns of Cachán y Maruata are known for Náhuatl textiles.

Wool (Lana)

This material, woven in backstrap looms, is used exclusively in the Purépecha region and partially in the Mazahua region in eastern part of the state. In Angahuan beautiful rebozos, blankets, echequemos, ruanas, and heavy woven fabrics are adorned with birds, flowers and geometric patterns. Heavy jackets are made by the craftspeople of Pichátaro, Santa Clara del Cobre, Cherán, Comachuén, Macho de Agua, Nahuatzen, Sevina and Charapan.

Backstrap looms produce the famed wide belts of Tarecuato, as well as pouches, belts and rebozos in Cuanajo, using an antique “dog leg” pattern. In the communities of Boca de la Cañada, Crescencio Morales and Macho de Agua, beautiful woolens woven on backstrap looms become rebozos, blankets, jackets, and knapsacks cross-stitched and embroidered with stars, border designs, deer, significant ornamentation of the region.

VEGETABLE FIBERS (FIBRAS VEGETALES)

Palm (Palma)

Introduced by the Spanish during the Colonial era, palm crafts were apparently developed in indigenous communities as part of the division of specialized crafts implemented by Vasco de Quiroga in Michoacán. Among the great variety of crafts made from palm, one product stands above the rest – the hat. Each region creates a version distinguished from the rest in materials, shape and size. An economic activity as well an affirmation of cultural heritage, the communities now known for hat-making are Jarácuaro, Zacán and Urén, the latter located in an area known as Cañada de los Once Pueblos.

Hatbands and linings are purchased in Pátzcuaro, Uruapan and Morelia. Beyond the sombrero making, the craftspeople also create a wide variety of decorative and utilitarian objects ranging from purses to folders and tortilla baskets.

Woven Maguey Fiber (Tejidos de Pita)

In Santa Cruz Tanaco and Tarecuato, strong knapsacks and bags are woven with maguey fiber, commonly called “pita” or “mizcalli.” These bags are smoothly woven in natural color. In Paracho the fibers of dyed maguey are woven to create the decorative elements of hats, bridles, reins, and cinches. In Pómaro, Ostula, el Naranjito and Cachán, these bags (“xiquipiles” or “carapes”), made from the same fiber, are used to carry pitchers and cobs.

Tule and Bullrush (Tule y Chuspata)

From time immemorial, the artisans of the Lake Pátzcuaro region have made diverse objects from tule and chuspata, a variety of bulrush. At first, they only produced bedrolls, the use of which continues to this day among indigenous peoples. At present, the craft workers of the communities of Ichupio, Puácuaro and San Jerónimo, make baskets, purses, tablecloths, tortilla baskets, floor coverings, and a variety of birds and decorative figures, representing images of daily life in the surrounding area.

Tule and chuspata production generally takes place in family workshops with materials obtained directly from the lakeshore, mainly along Lake Pátzcuaro. These objects reveal a great deal of creativity and variety and are sold in fairs and artisan markets in Michoacán as well as the rest of the country.

Reed (Carrizo)

From this reed, a species of the stalk of plants grown along the lakeshore, clothing hampers and baskets are made, most particularly in San Lucas Pío. In the community of Irancuataro, the men weave baskets for household use, heavy-duty baskets for harvesting strawberries and corn, and baskets used to carry bread, while the women dedicate themselves to weaving miniature objects inspired by traditional objects complemented by touches of imagination and fine detail.

Wheat Straw (Fibra de trigo o panicua)

The indigenous people of the Lake Pátzcuaro area began weaving representations of religious figures – Christs, Virgins, and saints – to adorn churches and altars. In celebrations such as Jueves Corpus, the artisans participate in the procession carrying their work. Wheat straw crafts – from hats to Christmas ornaments, baskets, tablecloths, and screens — are made in Ichupio, San Jerónimo Purenchécuaro, Tarerio, San Adrés Tziróndaro and Tzintzuntzan.

Willow twigs (Vara de sauce)

The towns of Uripitío and San Juan Buenavista are dedicated to the production of artisanal objects such as baskets, hats, wastebaskets, and chests made of willow twigs, branches, and agave fibers (“raicilla”) from the area.

TOYS AND MINIATURES (JUGUETERÍA Y MINIATURA)

Miniatures are the “little toys” that adults give more thought to than do children. Simply knowing the origin of these miniatures, their decoration and manufacture is fascinating. The miniature burnished pottery is polished in the same manner as the larger pieces, using a flint handed down throughout generations, an animal rib or hard piece of wood also serves as a polishing tool to smooth a fine finish. Miniatures are produced in all branches of artisan work: pottery, metalwork, woodwork, textiles, and vegetable fibers.

In the toy area, the little rag figurines made in Angahuan and Zirahuén portraying scenes of daily life are most famous, as are the spinning tops, yo-yos, and cup-and-ball toys made in Paracho, Aranza and Cherán, and the little wooden trucks made in Quiroga. In Paracho, painted rattles, acrobats, and other beautiful creations are made.

SADDLERY AND LEATHEWORK (TALABARTERÍA)

Dating from the Colonial era, this activity continues to be linked to horsemen and the countryside. The principal leather crafts include saddles, huaraches, embroidered belts, leather chairs, and “cueras” (a special kind of long deerskin coat), “spider” sandals, tooled belts decoratively stitched with a maguey fiber called “mezcalillo.” Leatherwork’s emphasis is upon huaraches and requires machines to cut and sew other more elaborate products.

FEATHER WORK (PLUMARIA)

Today in Tlalpujahua and Morelia can be found feather work, a craft that requires much patience, imagination, and observation. The artisans use bird feathers, wax, and acid, as well as a table, a little knife known as a “goat’s foot,” and scissors. The process consists of drawing a design on cardboard, leather or copper laminate, punching in that design, and then applying the feathers, one at a time, until the different colors and textures create the desired image. The principal themes are pre-Hispanic motifs.

STONEWORK (CANTERÍA)

“The art of working stone into reality is the tradition and inheritance of the towns….”

In Michoacán, stonecutting has embellished cities like Morelia. Stonecutters work to carve and polish stone, leaving their footprints throughout time, their works memorialized as much in architecture as it is in sculpture.

CHANDLERY (CERERÍA)

Wax crafts in Michoacán come in two forms: candles and wax sculpture. Wax objects are made in artisan workshops where secrets of the trade are guarded and transmitted from generation to generation. Candles are made from a mixture of wax and paraffin, melted into liquid, and into this mixture a wick is dipped into the waxy bath, cooled and dipped over and over until the desired thickness is reached. In another kind of chandler’s workshop, the liquid mixture is poured into plaster molds. These figures can be made into candles, arches, decorative pieces, or even rosary beads.

STRAW PAINTING (POPOTERÍA)

Today, straw painting continues in Tlalpujahua in small family workshops where the entire family participates, using rustic implements. The process requires several stages. First, straw is finely cut, and then it is dyed and dried in the sun. An original design is drawn on cardboard or posterboard, and a transparent layer of wax is applied over the posterboard. Using a small blade, the straw fragments are cut into pieces of two or three millimeters and carefully applied to the wax to fill in all areas of the design. The most frequent design themes are still life, Biblical and daily life scenes, and landscapes.

CUT PAPER (PAPEL PICADO)

During the Colonial era, many kinds of paper were brought from Europe, among them Chinese paper which was used as decoration during fairs and celebrations. One of the characteristics of this thin paper was the ease with which tiny cuts and borders could be made.

A very sharp tool determines the method of working the paper. Nowadays, small notches are cut with scissors over a folded piece of paper, but knives, punches and a curved instrument called a “gurbia” can be used to refine the contours or silhouettes. The most common designs are animals, plants, human figures, and legendary figures. Cut paper is used to adorn the streets and plazas of towns during fairs, fiestas, but it can also be found in home decor.

ARTISANAL BRANCHES (RAMAS ARTESANALES)

Pottery: burnished or polished clay, multi-colored pottery, high-fired pottery, glazed pottery, fired pottery, dotted pottery. Metalwork: jewelry, ironwork, hammered copper, brass. Wood: sculpture, woodworking, stringed music instruments, furniture, masks, lacquer, maque, columns, leather furniture.

Textiles: Embroidery, open and drawnwork, weaving, coats and bedspreads, shawls, hooked and crocheted work.

Vegetable Fibers: Hats, sombreros, tule, baskets, wheatstraw.

Other branches: Toys, leatherwork, stonework, waxwork, pattern-cut paper, cornleaf, bedrolls, ephemeral art, featherwork, straw painting.

where is Paracha, can’t find it on any map….??????

Apologies for the typo which has now been corrected! Thanks for helping to improve MexConnect, Editor.