Nothing better exemplifies the lively spirit of Mexico than a fiery shot of tequila, dashing charro horsemen and the stirring strains of a mariachi band. Jalisco is the heartland of these emblematic figures of the nation. Guadalajara, the state capital, puts them all into the limelight each September during the annual Encuentro Internacional del Mariachi y la Charrería.

The extensive program of festival events features gala concerts along with dozens of musical events scheduled at public venues in the metro area and other Jalisco communities.

To highlight the official kick-off, strolling mariachi troupes visiting from around the globe will be showcased in the traditional inaugural parade through downtown Guadalajara. Collateral activities include regular runs of the legendary Tequila Express railway line for tours to Tequila Herradura’s Hacienda de San José del Refugio production facilities. Charreada horsemanship contests, art exhibits and film complement technical workshops for participating musicians.

A full listing of program events is posted on-line on their website.

Exploring the Roots of the Mariachi

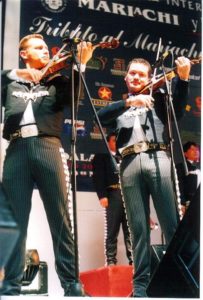

Close your eyes and rustle up the image of a mariachi band. You see a group of dashing gents — or gals — decked out in broad-brimmed hats, boots, and snugly fitted suits embellished with rich embroidery or rows of shiny silver buttons. You hear the lively strains of guitars and violins backed up with huge brassy sounds of trumpets. The emblematic musical groups of Mexico are like nothing else in the world. Yet the mariachi genre as we know it today has evolved dramatically over centuries from obscure roots buried deep in the history of the coastal highlands of western central Mexico.

Scholars who have looked into the origins of Mexico’s most emblematic music seem to agree that the mariachi sound as we know it today represents a fusion of autochthonous and European musical traditions, as well as an evolution from ancient to modern interpretive styles.

There is no question that the modern mariachi descended from the indigenous musicians who inhabited the mountainous region of western Mexico extended over the states of Jalisco, Nayarit, Colima and Michoacan. What remains under debate is the ethnic tongue — Coca, Pinutl or Náhuatl — and the precise geographic zone that gave birth to the genre.

When Franciscan missionaries arrived in the region between 1527 and 1529 they discovered a lively musical tradition already in place. Native tribes employed rudimentary reed and percussion instruments to add rhythmic fire to rituals honoring their ancient gods.

Realizing music’s potential as an aid for inculcating Christian doctrine, the Spanish friars began to foster musical instruction, introducing lyrical forms and string instruments of European origin. Tapping on their own creative juices, native craftsmen began producing crude versions of the foreign instruments, eventually creating the vihuela, a small guitar akin to the laud, and a huge bass guitar known as the guitarrón, both of which remain as distinctive elements of modern day mariachi troupes.

During the colonial era, with these instruments in hand, the musicians of occidental Mexico began developing their own peculiar interpretive style. Gradually sacred music gave way to a secular genre that was marked by irreverent lyrics expressed in the popular vernacular.

By the time Mexico gained her independence, a growing number of field workers in the region were putting down their tools at the end of the day to pick up instruments and entertain the masses. Still dressed in their crude cotton work clothes, huaraches and large straw hats, these self-taught musicians could earn a few extra centavos by setting a spirited melodic backdrop at popular festivities, cock fights and houses of ill repute. In various ecclesiastic documents dating from this era, disapproving priests recorded their impressions of such “wicked” carousing.

Cosme Santa Anna, curate of Rosamorada, Nayarit, described the trials and tribulations of his office in a letter penned to his bishop in May, 1852.

“Upon finishing the divine offices of my Parish on Holy Saturday I find in the plaza and in front of this very church, two fandangos, a gambling table, and men on foot and on horseback yelling like furies as a consequence of the liquor they drink, and all this makes for a most lamentable disorder. I know this is how it is every year on the most solemn days of the Resurrection of the Lord, and who knows how many crimes and excesses are committed in these diversions which are generally referred to in these part as ‘mariachis’.”

The excerpt is historically significant because it effectively debunks a long-held assumption that the term “mariachi” was derived from mariage (the French word for marriage), due to the genre’s popularity as form of entertainment for 19th century weddings. The missive demonstrates that the word “mariachi” had already become well ensconced in the popular vernacular a decade before the Emperor Maximilian arrived at the Port of Veracruz to head the French incursion.

Historians also point out that, like the religious sector, Mexico’s wealthy aristocracy during that epoch also frowned upon a musical style tagged with the derogatory term los violines del cerro to connote a despicable kind of native hillbilly music.

At this point mariachi groups mostly struck up their tunes on a variety of string instruments, including the harp along with violins and guitars. Reed instruments and drums, holdovers from earlier times, were sometimes included for good measure.

Mariachi music was virtually unknown in other parts of Mexico until the turn of the twentieth century, about the time interpreters of the genre began assimilating polkas, waltzes and other widely popular styles of the era into their repertoires. In 1905 the owners of the Hacienda la Sauceda sent a group of musicians from Cocula, Jalisco to Mexico City for a command performance at a birthday celebration for President Porfirio Díaz. To give them an acceptable air of respectability for the occasion, the musicians were provided with sarapes and red waist sashes to dress up their manta (unbleached cotton) working garb.

During the years of the Mexican Revolution, mariachi bands began belting out corridos, stirring narrative songs that often related significant events of the conflict. As the dust of battle began to settle, more and more mariachi performers set out to seek their fortunes in Guadalajara and the nation’s capital. They gained greater respectability by interpreting the works of renowned composers such as Manuel M. Ponce, Tata Nacho and Alfonso Esparza Oteo.

By the early 1930’s mariachi bands from Jalisco, notably those led by Cirilo Marmolejo, Concho Andrade and José Reyes, were well established in Mexico City and enjoyed a growing fan base. Some groups had cut recordings and many had spruced up their look by adopting the natty outfits of charro horsemen as standard dress. With the advent of radio, and the incorporation of the trumpets to help pump up the sound, the lively strains the mariachi were blaring far and wide across the nation’s airwaves before the decade was out.

The popularity of mariachi music was further enhanced by Lázaro Cárdenas who in his 1934 bid for the presidency employed groups to draw crowds along the campaign trail. The genre rapidly spread beyond national boundaries over the next decade as mariachi groups were featured in scores of motion pictures produced the in golden era of Mexico’s film industry.

Mariachi music became more refined in the latter half of the 20th century. The leading groups of today are made up of amply trained, proficient musicians who have traveled the globe and developed well-honed repertoires. Though still distinguished by their glitzed up versions of charro finery and stirring Mexican melodies, modern day mariachi groups are just as likely to stand out for their skilled interpretations of music by composers from distant lands, ranging from Bach to the Beatles.

However interesting its developmental history, what makes mariachi music so compelling is the sense of unbridled emotions it evokes. The huge, exhilarating sounds of brass and strings set off traditional songs noted for passionate lyrics telling of loves lost and found, of human heroics and base betrayals.

As an average, normally reserved Anglo-Saxon, I can’t help but feel a measure of envy upon witnessing the freedom with which Mexican men and women uninhibitedly burst into a mariachi sing-along. Here are people who genuinely know how to have fun. This ability to publicly pour out the heart has to be inherently good for the spirit. What a great, light-hearted alternative to the costly and often fruitless all-American panacea — therapy!