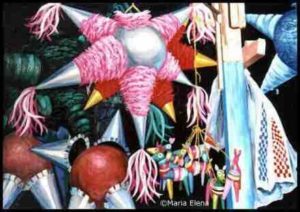

The Christmas season in Mexico is a time filled with delightfully colorful customs, among which one of my personal favorites is the traditional piñata -breaking that highlights most holiday festivities.

It’s a hoot to watch the youngsters unleash all that pent-up energy and, while on the one hand there’s a certain element of greed and agression implicit in these rough and tumble free-for-alls, the brighter side of human nature inevitably shines through at the end of it all.

More than that, the piñata is one of the finest examples of the extraordinary craftsmanship and creativity that so distinguishes Mexico’s people. Housewives, children, anyone with a creative bent can turn out a minor masterpiece devised with a few simple components–in this case a clay pot, paper and glue.

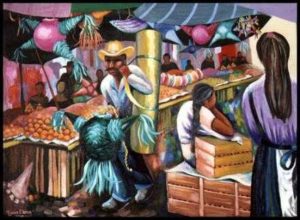

Every year my children and I buy a couple of piñatas to contribute to the decoration of Ajijic’s plaza and the January 6 Three Kings Day party thrown for all the kids in the village. A trip to the local market always leaves me astounded. It’s not just the wonderful array of piñata designs, but also, considering the time and effort involved, the give-away prices that these charming works of art draw–five dollars U.S. tops! We are rarely able resist the temptation to bring one home to add a festive touch to our patio.

Piñatas originated in Italy where the term “pignatta” means pot. An ancient custom during Lent was to hand out pots filled with gifts to farm workers. The practice later spread to Spain where it became customary to romper la olla (break the pot) on the first Sunday of Lent. The tradition became widely known as Domingo de Piñata.

Early missionaries first introduced the custom to Mexico in the immediate aftermath of the Spanish Conquest. The interruption of agricultural labors during the Conquista had brought on widespread epidemics and famine. Looking for ways to inculcate the Christian religion among the indigenous population, the Augustinian friars at the Acolman convent came upon a bright idea. They invited the hungry Indians to take whacks at clay pots filled with fruits and peanuts as an enticement to view theatrical presentations staged during the Christmas season to teach the story of the Nativity.

Before long bits of cloth and paper where being attached to the pots to make the breaking of the piñata more festive. This gave origin to the colorful piñatas that are now such an important part of many Mexican festivities.

The most traditional form for Christmas piñatas is the seven-pointed star representing the seven deadly sins. Thus the deeper meaning of breaking the piñata is considered to be the destruction of evil forces, the victory of good over evil. Covering the eyes of the person who tries to break the piñata is symbolic of blind faith.

Nowadays piñatas take many different forms. Lambs, burros, roosters, chickens, angels, wisemen, Christmas trees and Santa Claus figures are common for the holiday season. For birthdays and other festivities the possibilities are endless. Typical choices range from representations of characters from Disney or the latest rage in kiddy cartoons to pineapples (dotted with bottle caps wrapped in yellow paper), slices of watermelon, giant carrots, flowers, ships, airplanes, elephants, peacocks, mermaids, dolls and clowns.

The first step in making a piñata is to cover a rough clay pot with bits of newspaper and engrudo (a paste made from flour and water). Cones, cylinders and other shapes formed from paper are attached to the pot to create the basic figure. Strips of curled tissue paper, brightly colored metallic or crepe paper are affixed to decorate and add finishing touches to the figure.

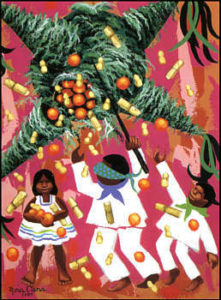

An opening is left to fill the pot with candies, peanuts and seasonal fruits such as oranges, tangerines, limas (a sweet variety of lime), a bits of sugar cane. A cord tied around the lip of the pot is used to hang the piñata to a rope that is strung up over the branch of a tree, roof beam or some other spot high overhead. An adult usually takes on the task of “driving” the piñata, pulling the figure up and down to delay the breaking of the pot and give more opportunities for each child to take his or her turn at bat.

Usually each batter is blindfolded, although this step may be omitted for the tiniest tots. An adult guides the youngster’s hands for an initial touch, then spins him or her around around a few times. The by-standers sing a round of the traditional piñata song:

No pierdas el tino.

Mide la distancia

Que hay en el camino.

Hit it, hit it, hit it!

Don’t lose your aim.

Measure the distance

That lies in the way.

This is followed by a chorus of “hot and cold” and usually misleading clues–“up, up;” “down,down;” “behind you;” “to the right,” and so on. The formula is repeated as the children take turns at bat and begin knocking off legs, arms, heads and other parts of the figure. Eventually someone will land a solid blow, breaking the pot and releasing a deluge of goodies. The on-lookers dive in en masse to scoop up the treats, frequently leaving the still blind-folded striker at the bottom of the heap. Its not unusual for at least one little one to get creamed in the process, resulting in some tears and howling. Often as not bruised knees and feelings will be consoled with a handful of sweets shared by a sympathetic friend or older sibling.

Personally, the piñata has been something of a saving grace for me as an extranjera (foreigner). In doing business in Mexico, I’ve often found people are bewildered by my name. Then I explain, ” Es como a la piñata–da-lay, da-lay.” That usually seems to get the message across–though I’m sure any number of folks have been left wondering whatever behooved my parents to call their child “whack it.”

Published or Updated on: January 1, 2000

who is the artist of these wonderful paintings, please?

These wonderful paintings date from 1999. The artist is “María Elena.” Unfortunately, we no longer have any contact information for her.

I found a couple of her articles here and confirmed that she is indeed the artist whose work I had admired and have been looking for again, ” lo, these many years”! Thank you, Tony.

sure do wish i could find more of her work to study!

For a story about her background in Mexico, see https://www.mexconnect.com/articles/684-patrick-dennis-art-lover/.

Her website was http://mariaelena-art.bizhosting.com/main.htm – it no longer appears to be active.

If I ever learn more about her, I’ll be sure to let you know.

Wow, thanks! I got the link to open!