Those who enter La Casa de la Cultura de Tulum during the month of March will find themselves face-to-face with the vibrant and complex culture of the Huichol people. The exhibit presents a rare opportunity for those residing in or visiting the southeastern city of Tulum to learn about Huichol culture, as it is seldom seen outside of the central western region of Mexico where this indigenous group resides.

“I think it is a privilege for Tulum that the local Maya people have the chance to find out about their Huichol brothers and sisters through an ethnographic exhibit,” says Giovanni Avashadur, director of La Casa de la Cultura de Tulum.

Avashadur hopes that people who visit the exhibit, “learn to value all that Mexico is.” The director also believes the exhibit will give viewers a better appreciation of the multitude of regional customs that exist in Mexico. As Avashadur explains, “Each region in Mexico is almost like a country – with different gastronomy, style of dress, traditions and customs. And what unifies us is something very particular – the ritual that is done with incense and the corn that gives us cultural identity as Mesoamerican people.”

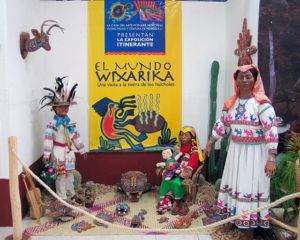

The Huichol exhibit, entitled Mundo Wixarika: una visita a la tierra de los huicholes (The Wixarika World: A Visit to the Huichol Lands), provides insight into the artwork and wardrobe of the Huichol people, as well as the customs and traditions of this fascinating group of people.

Despite the exhibit’s small size, it offers a stunning representation of Huichol life. Packed into the one-room display are approximately 200 objects that include handicrafts, clothing, food and ritual items. There are also nearly a dozen photographs of Huichols dressed in their traditional costumes that are on loan by the Comisión Nacional para el Desarrollo de los Pueblos Indígenas (National Commission for the Development of Indigenous Peoples).

Accompanying the visual aspects of the exhibit is a written section explaining various aspects of Huichol life. The text is currently available in Spanish, but English and Maya translations will be added during the course of the exhibit.

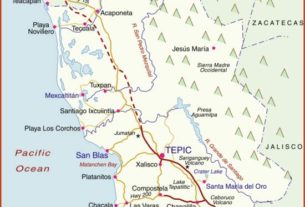

As the text explains, “The Huichols are one of the four indigenous groups that reside in the region known as the Gran Nayar, located in the southern part of the Sierra Madre Occidental Mountains. The Huichols call themselves Wixarika or, in plural form, Wixaritari, a word that’s meaning is unknown but from which the term Huichol is derived.”

According to the General Census of Population and Housing for the year 2000, there are 16,932 Huichol speakers in the state of Nayarit; 10,976 in Jalisco; 1,435 in Durango; and 330 in the state of Zacatecas; which adds up to a total of almost 31,000 Wixarika speakers nationwide.”

The Huichols have traditionally resided in the four abovementioned states of Nayarit, Jalisco, Durango and Zacatecas. Their territory, due to its mountainous location, offers little accessibility.

As the exhibit text states, “Due to the geographical conditions, roads are scarce. There are no paved highways, which makes it difficult to transport and distribute products.”

A small map of the Huichol territory and a photo of the steep Sierra Madre Mountains are on display, giving viewers a sense of the rugged geography that comprises the Wixarika terrain.

The exhibit’s main visual display is divided into several different scenes that use mannequins to depict the conditions in which the Huichols live, as well as their manner of dress, foods eaten and rituals practiced.

On one side are two children dressed in typical Wixarika outfits. The boy, who is posed in a standing position, is dressed in an embroidered cotton shirt and white cotton pants. He is wearing a wide-brimmed palm hat decorated with feathers, which is an accessory that Huichol males typically wear. In addition to feathers, the Wixaritari also decorate these hats with flowers and squirrel tails. The girl, who is sitting, is wearing a simple ensemble comprised of a red cotton blouse with a matching green skirt. She has two dolls in her lap and one at her feet that are also dressed in Huichol attire.

To one side of the children is a woman costumed in a short cotton blouse and flowing skirt, which is the characteristic style of dress for Huichol females. Her outfit is embroidered with colorful deer and bird designs and she is barefoot, which is customary of Wixarika women. She is wearing a bright orange kerchief that covers her hair and is bedecked with intricately detailed jewelry that is made of small beads.

These tiny beads, which are known as chaquira or seed beads, play an integral role in Huichol handicrafts. In addition to beaded jewelry, the Huichols also create ornate masks and other artisanal objects that are entirely covered in seed beads. The creation of these eye-catching pieces involves the skillful placement of each individual bead on a layer of beeswax or Campeche wax that coats the surface of the objects. This process results in stunning handicrafts that are covered in a dazzling array of vibrant beaded patterns, which often represent important symbols in the Huichol culture like the peyote and the deer.

In addition to their seed bead pieces, the Huichols are also renowned for their yarn paintings. This artwork is created in a similar fashion to the beaded handicrafts. A piece of wood or a mask is covered in wax and then covered with colorful strands of yarn that are coiled into different designs.

Handicrafts play a prominent role in the Tulum exhibit, as they are one of the most recognizable facets of the Huichol culture. In the first scene mentioned above, the two children and the women are surrounded by resplendent beaded pieces and yarn paintings.

The Wixarika artwork is also on display in the exhibit’s central scene, which is comprised of three different mannequins in a typical Huichol village setting.

On the right side is a Huichol couple who are posed behind an assortment of Wixarika handicrafts, including beaded eggs, ceremonial bowls and jewelry, as well as small yarn paintings and tsikuris. A tsikuri or ojo de dios (God’s eye) is comprised of two wooden sticks that form a cross shape and have yarn wrapped about them in diamond-shaped designs that represent eyes.

On the left side of the scene is a kneeling woman who is holding a basket filled with ears of corn. In front of her are more ears of corn and a variety of other foods typical of the Huichol diet, such as eggs, grains, tomatoes and tortillas. Next to the food is a metate, which consists of a stone slab and a pestle, or mano used to grind up corn to make tortillas.

The background of the scene is comprised of two photographic reproductions, which allow viewers to see a stone and mud house that is characteristic of the dwellings in a Huichol village. “The majority of the houses have one room that serves as the bedroom and also as the kitchen,” according to the exhibit text. “In some places, however, there are houses with additional rooms. In hot weather, the Huichols tend to sleep outdoors or in the reed structures where they store grains. Next to the dwelling they build tiny adobe houses called ririki, ‘houses of god,’ which are temples dedicated to their gods and ancestors.”

Religion is an integral part of Huichol culture, as evidenced by the final scene of the exhibit display, in which a warakami or shaman is represented in a ritual setting. In this scene, a shaman is posed standing behind a drum ringed with a garland of flowers, a cigarette in his hand. On one side of the shaman is a bonfire and on the other side are the ceremonial objects, including ears of corn and peyote. The photographic background of this scene shows other warakamis also engaging in the ritual ceremony.

One of the most important ceremonies of the Huichols, according to the exhibit text, is “the celebration of the toasted corn, which is carried out during the clearing and burning of the fields. In this ritual, the union of the religion’s three central elements – corn, deer and peyote – is shown.”

“For the indigenous Huichols, the culture that we are is very important to us,” explains Catalina González Hernández, a 24-year-old Huichol woman who was the guest of honor at the exhibit’s opening night on February 24. González Hernández, who is from San Sebastián in the state of Jalisco, moved out of her village to southeastern Mexico just two months ago. “I am far away (from home), but I see this and I am moved,” González Hernández comments about the exhibit. “I see my culture and what most interests us – they have the peyote flower, the corn, everything. It is perfect. It is beautiful.”

For other visitors, the exhibit has provided a chance to learn about a culture that is totally new to them. “We definitely don’t have this in England,” noted Penny McGregor, who arrived from Oxford in mid-February to teach English in Tulum. “So this is very interesting. It’s brilliant, actually.”

The Mundo Wixarika exhibit will be on display in la Casa de la Cultura de Tulum until March 24 and then will move on to other locations in southeastern Mexico. This traveling exhibit was organized by La Casa del Arte Popular Mexicano in Cancun and marks the first collaboration of this kind for both museums.

“It is part of a project that we started to plan last year – extending the museum’s borders by having a traveling exhibit,” explains Guadalupe Quintana Pali, director of La Casa del Arte Popular Mexicano.

“We hope that in this region of Maya culture, where inhabitants from all over the country and the world have come to live, that we will learn about that ancient Mexico – of other races and traditions – that is still alive in other regions of the country,” says Quintana Pali. “We have the habit of taking these cultures lightly, of focusing on how pretty their handicrafts and clothing are, but we should really try to understand who they are.”

Adds Quintana Pali, “we are a very rich country. We have a richness that is more than cultural; it is human.”

Photos by Kinich Ramirez © Kinich Ramirez 2006